“The Mason Children, David, Joanna and Abigail”

December 19, 2014

This oil painting depicts three children (one boy and two girls) posing with props is one of a small number of paintings from New England showing cultural icons of Puritan society. It is carefully detailed and fascinating to look at. There is an interaction between these figures: gazes that cross each other, the distortion of the girls’ hands make it seem like they are reaching to hold hands, to give each other support, subtly demonstrating a silent bond despite a space between them. The separation of the girls from David is marked by the walking stick, which serves to separate the two sexes.

The composition tells the viewer about the time and society in which the painting was produced. The girls are symmetrically posed with Joanna set slightly forward on the plane creating a one-point linear perspective indicated by the floor pattern. David’s posture further adds distance, as well as indicated the youth’s predestination to be someone of prominence in his community as shown by the enlarged stomach, then a sign of prosperity.

The use of color is subdued but exciting at the same time. The chiaroscuro is dramatic; values are extreme between dark rich browns and greys and the intensely light whites and beiges, with one exception – the red hue – that is used on the girls. This intense red stands out as a strong statement for during this time wearing red symbolized passions not to be shown in public. However, I believe the use of red in this picture reflects the passion of our county’s youth.

The textures in this work are precise and clean from the contour lines to the lovely modeling of the skin, to the softness of the hair. The textures of the delicate lace, fine leather, shiny ribbons, heavy fabrics, and shear stockings demonstrate the skill of the artist. “The Mason Children, David, Joanna and Abigail” could be a symbol of the first American frontier, for it is a group of people who have the garden, and who long to have a society with all of its structure. Society is shown through the cane and fan; religion is shown with a rosary, and the garden is symbolized with the red rose. Even at this point, Colonials needed to be bound by the restrictions of civilizations symbolized by the red ribbons that bind the girls’ neck, arms, and feet. For me the unknown Freake-Gibbs Painter has done a brilliant job in conveying the youth of America.

“The Mason Children, David, Joanna, and Abigail” (circa 1670) at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (online):

http://www.wwnorton.com/college/english/nael/17century/topic_4/illustrations/immason.htm

Volland Publishing and Women artists

December 18, 2014

German-born Paul Frederick Volland established his successful greeting card company in Chicago, Illinois in 1908. However, he hit the jackpot with a series of children’s books about a loveable rag doll named Raggedy Ann. Volland offered opportunities for many women to enter the publishing industry as writers and illustrators. The following are two lesser-known women who also found success with Volland Publishing. M. T. Penny Ross was an active illustrator between 1900 and 1920. The vibrant colors and whimsy of Ross’ illustrations published by the P.F. Volland Company, which included flower children, “Mother Earth’s” children, and our bird children, captivated young children and taught them about nature with easy to remember rhymes.

Pre-1910 – Animal Children

1910 – The Flower Children, P. F. Volland

1912 – Bird Children, P. F. Volland

1914 – Mother Earth’s children, P. F. Volland

1914 – Year with the fairies, P. F. Volland

1915 – Loraine and the Little People of Spring, Rand McNally

1916 – I Wonder Why?

1985 – Get down and come in, Author

Elizabeth Gordon (1865-1922) lived in Chicago Illinois. Began writing as a contributer of special articles from the West for the Portland Transcript, the Bangor Courier, and others, She was the editor of the Children’s Tribune in Minneapolis, 1901-04 and the editor for “Babylan” department of Junior Instructor Magazine 1920-21, and assistant literature cricit for Cumulative Index. She was a member of the League American Pen Women, Storytellers League (Los Angeles and Chicago), Women’s Press Club, Illinois Women’s Press Association, and Midland Authors.

1879 – Among the flowers: a poem

1881 – The world’s future, or the Union leader

1905 – (The) influence of Lucretius

Pre-1910 – Animal Children

1910 – The Flower Children, P. F. Volland

1911 – Some Smile: a Little Book, W.A. Wilde

1912 – Bird Children, P. F. Volland

1912 – Just you, P. F. Volland/G.W. Parker

1913 – Bood of Bow-Wows, M. A. Donohue

1913 – Four Footed Folk

1913 – Mother Earth’s children, P. F. Volland

1914 – Butter Fly Babies, Rand McNally

1914 – Dolly and Molly and the farmer, Rand McNally

1914 – Dolly and Molly at the circus, Rand McNally

1914 – Dolly and Molly at the seashore, Rand McNally

1914 – Dolly and Molly on Christmas, Rand McNally

1914 – Granddad Coco Nut’s Party, Rand McNally

1914 – Watermellon Pete, Rand McNally

1915 – Loraine and the Little People of Spring, Rand McNally

1915 – A Sheaf of Roses, Rand McNally

1915 – What We Saw at Madame World’s Fair, S. Levinson

1916 – King Gum Drop or Neddies

1916 – I Wonder Why?

1917 – Wild Flower Children, P. F. Volland

1919 – Billy Bunny’s Fortune, P. F. Volland

1920 – Buddy Jim, Wise Parslow/P. F. Volland

1920 – Johnny Mouse’s trip to the Moon, P. F. Volland

1920 – Turned-Into’s, P. F. Volland

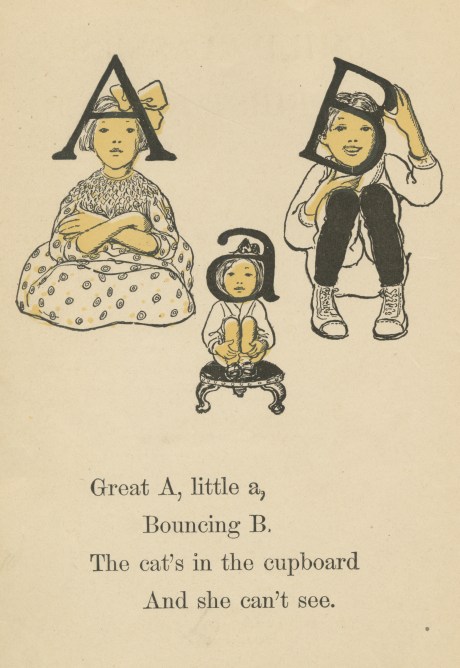

Henriette Willebeek Le Mair (1889-1966)

December 17, 2014

Born in Rotterdam, Henriette Willebeek le Mair was the daughter of a wealthy corn merchant. Her early childhood was comfortable and many of the motifs for interiors and scenes depicted in her illustrations could be traced to her own nursery. She was influenced by the work of French children’s illustrator Maurice Boutet de Monvel, and she wanted to take drawing lessons from him, but when they met, he suggested that she should develop her own style.

Known as a hard worker, she was a gifted linguist, sportswoman, and musician. In her twenties she taught a dozen young children in her home, and these children were her models as she developed her graceful style. She was fastidious in work, and completed countless sketches before she was finally satisfied. Miss la Mair was commissioned to create a series of images for color plates to advertise Colgate. The publishers were so impressed by the sumptuous illustrations that they asked A.A. Milne to write a series of pieces around her work.

In 1920, le Mair married Baron van Tuyll van Serooskerken, a Sufi, and she joined the mystical Muslim movement a year later, an involvement that change the character of her artwork and dominated her later life as she devoted herself to travel, religion and helping the poor.

1911 – Our Old Nursery Rhymes

1912 – Little Songs of Long Ago

1913 – Little People

1914 – The Children’s Corner

1915 – Schumann’s Album of Children’s Pieces

1917 – Dutch Nursery Rhymes

1925 – A Gallery of Children

1926 – A Child’s Garden of Verses

1939 – Jtakata Tales

Paper Doll Artist: Fern Bisell Peat (1893-1971)

December 16, 2014

Know for her beautiful paper dolls, such as Rad Doll Sue (1931 for Harper Publishing Co.) and Sally Lou (1931 for Saalfield Company) Fern Bisel Peat grew up in the Midwest. She graduated in fine arts from Ohio Wesleyan University in 1915, and commenced with her career in commercial art with the Birge Walpaper Company and Columbus Coated Fabrics Company, both in Ohio.

She married her college sweetheart, Frank, in 1917 and they lived in the Cleveland area until 1961 when they moved to Florida. They had three children, Billy, Joan and Phyllis. When Joan was born, Frank made some miniature furniture for the nursery, and Fern decorated the walls with appropriate designs. Soon their friends were asking the Peats to decorate their children’s rooms, so in 1921, the Peats established the Peter Pan Studio which specialized in decorating children’s rooms. The Peats painted murals in more than 200 private homes, two Akron hospitals and many childrens institutions in the area. While working on the hospital murals, Saalfield commissioned Fern to illustrate childrens books.

Fern was asked if she ever used her children as models, and she said that they frequantly appeared in her illustrations, but her youngest daughter, Phillis was a model for Round the Mulberry Bush.

1928 – Jiji Lou

1929 – Animal Caravan, Saalfield

1929 – Mother Goose, Saalfield

1930 – Christmas Carols, Saalfield

1930 – A Christmas Carol, Saalfield

1930 – Fireside Stories, Saalfield

1930 – Tanglewood Tales, Saalfield

1931 – The Cock, the Mouse and the..., Saalfield

1932 – Little Black Sambo, Saalfield

1933 – Picture Story-book, Saafield

1937 – Wynken, Blynken and Nod, Saalfield

1939 – Bunny’s Book of Best Stories, Saalfield

1940 – A Child’s Garden of Verses, Saalfield

1940 – Four Stories that Never Grew

1943 – Birds, Saalfield

Sarah S. Stilwell Weber’s culminating works

December 14, 2014

Kiddie Kar Verses (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippencott Company, 1920) by Richard J. Walsh (second husband of Pearl S. Buck, 1892-1973) was illustrated with color plates and elaborate decorative borders by Sarah S. Stilwell Weber. She created elaborate borders for mirrored two-page spreads (the left page showed her initials backwards with color illustrations (copyrighted by H.C. White Co., 1920) with Walsh’s series of nine jingles to be read aloud to children.

The Musical Tree (1925), probably Sarah’s last major work, contains songs and pictures by the artist and her husband Herbert. The Musical Tree shows how Sarah’s career unfolded: she was able to synthesize elements of childhood utilizing all of the experience and illustrative styles that converged through her twenty-five year career. “Lady Fair,” for the story of Sleeping Beauty is a melodious work, blending patterns to create a sort of line rhythm that is busy with motion yet serene in spirit. Sarah by this time hints at faces with just a few lines – they become like the faces of dolls in her earlier works – vessels for a child’s imagination.

Illustration of Bluebeard’s Wife from the Musical Tree.

Although Sarah’s work was well received, her shy and modest demeanor seemed to lead her out of the mainstream art world once she married and started a family. Sarah Stilwell Weber remains sweetly enigmatic, remembered for her graphic art and fine line drawings that captured the spirit of children at play. Of all of her works, “Happy Days” with its simple energetic optimism retains an attraction.

Sarah Stilwell Weber created enticing portrayals of children at play that appeared in important magazines of her day, including St. Nicholas, Vogue, the Saturday Evening Post, Harper’s Magazine, and Scribners’ Magazine. Stilwell Weber’s work often integrated inanimate objects including dolls, toys, and books to work through issues of growing up. Her work, almost forgotten, remains an exciting document of children, childhood, and child’s play at the turn-of-the-twentieth century. Her work is worthy of further study as an example of illustrations that chronicle healthy children.

Sarah’s style

December 13, 2014

Sarah S. Stilwell Weber, according to one contemporary critic, was the “delineator of fully clothed little girls.” This was a significant distinction. She was a graphic artist who expanded American illustration with a unique decorative style throughout some of the most exciting periods in the modern history of American art. Her early work reflects many themes that were common to the Philadelphia area at the turn-of-the-twentieth century, stemming from the post-Civil War urbanization. To this, she added the fragility of dreams and fairy tale illusions with undercurrents of turbulence. She toyed with the garden theme (from Art Nouveau) in much of her early decorative work, reflecting the romantic spirit with its rhythmic curvilinear surface movement, often containing line and pattern within an enclosed space.

Sarah’s work after her mentor Pyle’s passing, when accompanied by her own poetry, prose, and music, creates a feminine view of childhood that blends the subconscious dream lives of children with active play lives. Her compositions of children playing and children reflecting in natural settings often included ordinary places like backyards, shorelines, and meadows of flowers. She delineated the subconscious dream lives of children along with their active play lives to illustrate how children naturally used objects including dolls, toys, and books to work through issues of growing up. She utilized the three elements coming from the Art Nouveau movement: symbolism, naturalism, and decorative ornamentation. Sarah’s work revealed the spiritual side of children.

As an artist, Sarah chose to place realistic children in magical settings. Even before Jane’s birth, Sarah had a sense of how children think, play, and grow intellectually. She tapped the magical worlds found in classic fairy tales – her exotic themes brought her notoriety. While fairy tales often present terrifying situations where child characters cope in a threatening world, Sarah’s illustrations present nurturing feminine spirits that encouraged emotional growth through passive play.

Scribners’ Magazine for January 1913 featured, “Famous Playgrounds,” which marked a significant shift for Sarah. Labor saving devices such as the telephone, electric lights, and the automobile, along with events like the national suffrage movement, and later the Spanish influenza epidemic, and World War I, changed not only how Americans lived but also how they viewed leisure time and child rearing. Much of Sarah’s work expressed a longing for freedom and private dream spaces or hideouts found only in a child’s world.

When a reader thumbs through the pages of a magazine, Sarah’s layouts pop out. The reader pauses to look at her work. She had the ability to block out powerful concepts into subtle visual essays. For instance, “Famous Playgrounds” would appear to be just a series of pictures of children playing in parks. The children could be playing anywhere, but the parks depicted are urban gardens: Jardin du Luxembourg in Paris, Kensington Gardens in London, and Central Park in New York City. What looms behind the child’s play is the encroaching fast pace of city life. Her painting of Central Park reveals the transition from the horse and carriage to the car – the skyscrapers appear to be crowding out nature. In the corner of one illustration lurks another message: a bird sits on a sign posted on the grass as a squirrel looks on – the sign reads, “Keep Off.”

Sarah Weber and the Saturday Evening Post

December 12, 2014

Saturday Evening Post editor George Horace Lorimer spotted Weber’s talent and became her patron, offering Sarah a contract to contribute covers scheduled on a regular weekly basis – but she declined – unsure of her ability to maintain strict deadlines along with family obligations, while retaining her artistic integrity. Stilwell-Weber toyed with themes of innovative twentieth-century play where inanimate objects became private vessels into which hopes and magical make-believe dreams were distilled. On Christmas Day, 1909, she introduced Post readers to a boy playing with new toys. Alphabet blocks, along with a clockwork duck, a football, and toy trains lay idle, as he curiously figures out the working of his new little red airplane. Gardens, shorelines, and even fishbowls, become symbolic places forever on the threshold of becoming whatever the child breaths into them.

Later, Norman Rockwell (1894-1978) would sign on to become their resident cover artist and make a name for himself with paintings of rural and small town life. However, over the years Sarah still created about sixty covers for The Saturday Evening Post between 1904 and 1921. Even when women had no vote, as a magazine illustrator, Sarah earned an equivalent salary to a Supreme Court justice in 1910. As a mother, she brought realism to the subject of childhood when other artists including Norman Rockwell marketed nostalgia. In 1910, Stilwell Weber’ cover illustrations from the Saturday Evening Post during 1909 and 1910 were used in Ethel C. Dow’s Mother’s Hero (New York: Barse & Company).

Stilwell marries and starts a family

December 10, 2014

Sarah S. Stilwell was a beautiful petite dark-haired woman, who often wore her hair braided long down her back. Pyle advised her not to marry because it would interfere with her creative life as an artist. However, Sarah’s sister Gertrude remembered how newspaperman-turned-English teacher Herbert S. Weber “wooed her with Chopin nocturnes.” The two married and had a daughter named Jane. The Weber family settled into a private life in Philadelphia where Sarah had a studio in 1909, and they traveled to Nova Scotia for summer vacations. Many of Sarah’s Post covers feature favorite model – Jane – playing in a variety of situations. Her niece, Elizabeth W. Disston remembered Sarah as a “self-effacing woman, loving the innocence of little children believing in the dream-like quality of fairyland.”

Although Stilwell Weber’s early work was innovative and well received, she seemed to step out of the mainstream art world when he married and started a family. Stilwell remains somewhat enigmatic, remembered for her graphic art and fine line drawings that captured the spirit of children at play. All of her compositions depict a simple optimism from a carefree way of life through movement in the designs. She is remembered for her enticing portrayals of children in dreamy landscapes. Her work remains an interesting document of children, childhood, and child’s play at the turn of the twentieth century. Her mystique lies in her ability to enter and express childhood in a variety of ways without loosing innocence or freshness.

Stilwell Weber illustrated Georgia Alexander’s First Reader: Child Classics (1909), containing nursery rhymes, plays, fairy tales, and historical sketches. In over sixty illustrations, a full range of styles deftly creating a cohesive visual package that brings together diverse subject and literary formats. Stilwell Weber’s Cinderella, with a long hair braided down her back, captures a moment of metamorphosis when a child emerges from a protected cocoon to meet the world with optimism for a better tomorrow – and this illustration could be a self-portrait of Sarah who went from humble rural origins as a harness-maker’s daughter to a highly successful commercial illustrator.

Child Classics, Frontispiece

Child Classics, illustration of Cinderella found on page 15.

Child Classics, illustration of Goody Two-Shoes found on page 35.

Child Classics, illustration of the Little Red Hen featuring a classic Stilwell Weber pinafore, found on page 76.

Sarah’s career began at a time when young women did not actively pursue high-paying careers as illustrators – even if they were accomplished artists. Her work reflects homey American themes – a reaction to post-Civil War urbanization. Her decorative work often consisted of rhythmic surface movement and curvilinear pattern work drafted within enclosed spaces. To this, she added the fragility of dreams and fairy tale illusions with their undercurrents of turbulence.

Dodge and Stilwell collaborate on “Rhymes and Jingles”

December 9, 2014

The 1904 edition of Rhymes and Jingles by Mary Mapes Dodge (1831-1905) was an exciting little volume with illustrated binding in gold embossed hunter green that features a little girl wearing a big decorated hat that attracts some whimsical butterflies. Beginning in 1874, Dodge served as editor of St. Nicholas magazine; she was credited with turning it into an American classic that spotlighted quality children’s authors and illustrators. Rhymes and Jingles was generously illustrated in black and white by Sarah S. Stilwell who employed a variety of artistic styling that reflected Howard Pyle’s illustrative sensibilities, but created a cohesive youthful take on Art Nouveau featuring a cast of fairy ladies, several working mice, and one awesome bubble-gum-popping girl:

Little Polly, always clever,

Takes a leaf of live-forever;

Before you know it

You see her blow it,

A gossamer sack

With a velvet back

How big it grows

As he puffs and blows!

But have a care,

It is full of air

Unless Polly should stop

It will crack and pop;

And that’s the end of the live-forever;

But little Polly is very clever.

Dodge described Stilwell as a “well-known artist” in 1904.

Source: Mary Mapes Dodge, Rhymes and Jingles (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1904).

“Happy Days”… Children at Play

December 8, 2014

My first introduction to Stilwell’s work was her pictorial essay in the December 1903 issue of St. Nicholas: An Illustrated Magazine for Young Folks called “Happy Days.” Perhaps her best-known early composition, “Happy Days” was comprised of portraits of children occupying their time in ordinary settings: scenes of a backyard hammock, a meadow of flowers, and walking along a rain-soaked street are juxtaposed to a line drawing of children playing a circular singing game. The captions read like a prayer:

I love the world when the sun shines

Down on the quiet ground,

When I hear the grass-bugs chirp at my feet

And the end of a distant sound.

I love the world when the wind blows.

When it tosses my hair about.

When it blows my hat off,

And my ribbons crack,

And I laugh and run and shout.

I love the world when the rain falls.

When the streets are all mud and ooze.

When I need my umbrella and mackintosh

And my shiny, new overshoes.

I love all the days

Of the beautiful world,

Every day – every hour and minute

I could go on living forever – and never

Grow weary of any-thing in it.

“A Garden of Childhood” and “Happy Days” both contain memorable illustrations of a little girl reclining in a hammock with a book or a doll – suggesting that the girl is at peace embraced at the center of her world.