women vote women vote… 100 years

August 18, 2020

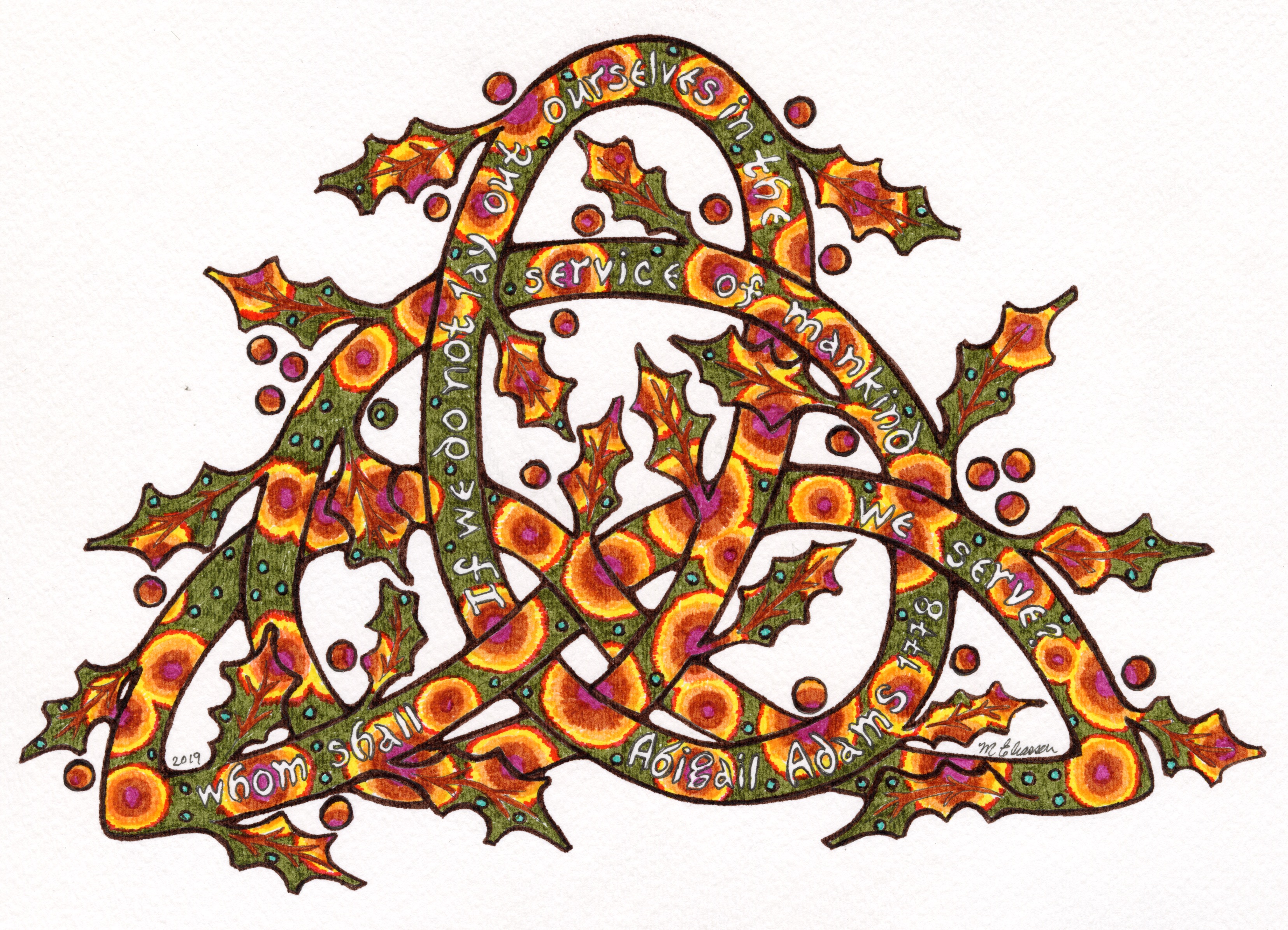

Right on Abs!

October 9, 2019

Designed by Meredith Eliassen, 2019.

A Girl in her Pinafore can go anywhere!

December 6, 2014

Sarah S. Stilwell-Weber was foremost a visual storyteller, her imagery reflecting fragile spontaneity of dreams and fairy tales with undercurrents of real tensions of the Industrial Age so that actions in her compositions jump beyond the boundaries of the page. A girl in her pinafore could go anywhere… and accomplish anything. Pinafores, wraparound garments like aprons were worn to protect girls’ clothes from soil; they were requisite for active outdoor play. Over the years, Stilwell-Weber turned this ordinary functional garment into an elaborate fashion statement with intricate floral fabric designs, laces, and even fringe.

In 1899, Stilwell illustrated Edward Sanford Martin’s The Luxury of Children and Some Other Luxuries (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1905). Humorist, poet, and essayist Edward Martin (1856-1939) offers insights on children and childhood that Stilwell illuminates with seven black and white plates tinted alternately with orange and green with images of children at play, study, meals during daily life. The Frontispiece “Easter-time” shows a girl with Easter eggs nested on a pillow on a sofa (green); “Feeding the chickens” shows a girl wearing a pinafore feeding chickens in front of a stone wall (orange); “A New Day” shows a girl rising in her bed from beneath a fluffy patchwork quilt and looking out the window at the new day (green); “Breakfast” shows a girl eating cereal as her mother places a glass of milk on the table featuring popular “Blue Willow” patterned dishes; “In School” features the same girl in a pinafore working on a lesson on cursive writing in a reader working on a small slate; “Sewing” shows a girl seated in a big chair piecing together squares for a quilt; “In Paddling” is a misty images of a girl wading along a shoreline; and “Shadow-Time” shows a girl seated on her mother’s lap in an embrace before bedtime.

Now, an aside on doll imagery for consideration

December 4, 2014

In 1896 Caswell Ellis (1871-1948) and G. Stanley Hall (1844-1924) published a survey that focused on how children play and interact psychologically with dolls. It also examined child rituals related to doll play such as naming, feeding, discipline, and how children created imaginary social lives for their dolls, which would be illuminated in illustrations by Sarah S. Stilwell. The Ellis & Hall study found that perhaps nothing so fully opens up the child’s soul in the same way that well-developed doll play does. Ellis and Hall reported: Whispered confidences with the doll are often more intimate and sacred than with any human being. The doll is taught those things learned best or in which the child has most interest. The little mother’s real ideas of morality are best seen in her punishments and rewards of her doll. Her favorite foods are those of her doll. The features of funerals, weddings, schools, and parties which are re-enacted with the doll, are those which have most deeply impressed the child. The child’s moods, ideals of life, dress, etc., come to utterance in free and spontaneous doll play.

The Ellis and Hall study found that the educational value of dolls was enormous, and that doll passion was strongest for children between the seven and ten years of age, reaching its climax between eight and nine. Ellis & Hall commented that a child’s doll: Educates the heart and will, even more than the intellect, and to learn how to control and apply doll play will be to discover a new instrument in education of the very highest potency. The study concluded that: Many children learn to sew, knit, and do millinery work, observe and design costumes, acquire taste in color, and even prepare food for the benefit of the doll. Children who are indifferent to reading for themselves sometimes read to their doll and learn things they would not otherwise do in order to teach it — or are clean, to be like it.

Let me briefly visit the seemingly conflicting issue of control related to doll play: while Victorian parents used dolls as instruments of control so that girls were taught the mundane tasks of domesticity — for girls — dolls became vehicles for flights of fancy. During doll play, girls made and controlled the rules for play, and dolls provided girls with freedom for self-expression. The irony was that with this imagined-freedom and control in doll play, girls also received the practical socialization and instruction that parents wanted them to get.

Dolls became neutral vessels for the children’s imaginations where they can work through the issues of their daily lives. The essence of “childness” is universal and timeless – children who can happily entertain themselves with an empty box once the novelty of the toy contained within that box has worn off; having the ability to create imaginary worlds that hold very real solutions; and these inner worlds are necessary. When our toys create total-entertainment-experiences, we do not need to develop our own imaginations, and thus, we loose our ability to imagine. If you look at creative people today, they need a lot of time alone – for whatever reason – this is the time and place where they develop ideas. When children are young, we need to provide them with space for imagining so they can discover practical insights and prepare for the adult world.

Source: Caswell Ellis and G. Stanley Hall, “A Study of Dolls,” Pedagogical Seminary 4 (December 1896): 129-175.

Paper dolls

October 29, 2014

As early as the mid-eighteenth century hand-painted figures and costumes created on paper by dressmakers illustrated current designs in London, Paris, Vienna and Berlin. A London advertisement proclaimed a new invention called the “English Doll” in 1791, that was a young female figure, eight inches high, with a wardrobe of underclothes, headdresses, corset and six complete outfits. S & J Fuller in London produced the first paper doll for their “Temple of Fancy” at Rathbone Place in 1810. Little Fanny from The History of Little Fanny was a popular paper doll with a single transposable head, seven costumes, and a number of hats, as cut outs that were used in the telling of the story.

Belcher of Boston was the first American company to publish paper dolls with their The History and Adventures of Little Henry published in 1812. Cinderella, or, The Little Glass Slipper: Beautifully Illustrated with Figures (London: S. & J. Fuller, 1814) captivated little girls with paper dolls. During the 1820s, boxed paper doll sets were imported from Europe to America. McLoughlin Brothers, established in 1828, was the largest manufacturer of paper dolls in the United States. McLoughlin’s earliest paper dolls were printed from wood blocks that had been pirated from British publishers. McLoughlin Brothers and British publisher Raphael Tuck continued producing paper dolls until the twentieth century. McLoughlin Brothers continued developing paper dolls, along with children’s story and playbooks after its sale to Milton Bradley in 1920.

Peter G. Thompson was a smaller company that published paper dolls in the 1880s. Raphael Tuck was perhaps the best-known manufacturer of finely lithographed items patented their first paper doll, a baby with a nursing bottle in 1893. Paper dolls appeared in advertising, some die-cut, and as cards to cut out. Paper dolls were featured in advertising for Lyon’s coffee, Pillsbury flour, Baker’s chocolate, Singer sewing machines, Clark’s threads, McLaughlin Coffee and Hood’s Sarsaparilla.

Godey’s was the most widely circulating monthly American magazine edited by a woman (Sarah Josepha Hale between 1837 and 1877) prior to the Civil War that dictated fashion and literature trends for generations of women. Godey’s contained hand-tinted fashion plates, clothing patterns and sheet music, and was carried to the frontier. In November 1859, Godey’s Lady’s Book was the first women’s magazine to publish a paper doll. Illustrated in black and white, their paper doll accompanied with a page of costumes for children to color. Good Housekeeping was a major publisher of paper dolls beginning in 1909. McCall’s Magazine developed the most popular paper doll character Betsy McCall spotlighting many artists from 1904 to 1926 in their cut-and-fold McCall Family series. Artist Kay Morrissey developed sweet-faced Betsy McCall, which debuted in 1951. Betsy McCall, followed the original function of paper dolls by modeled fashions that could be made with McCall’s patterns. Paper dolls appeared in newspapers during the Great Depression and were cut out by children who often made elaborate paper doll scrapbooks.

The Mother of Home Economics: Catharine Beecher

October 10, 2014

Catharine Beecher (1800-1878) was considered by many to be the mother of home economics in America. Beecher became an influential shaper of American middle-class female culture during the antebellum years, by lobbying for higher education for women and the advancement of female teachers in public education. More importantly, Beecher intellectually reconciled the status quo for female subordination to values of American democracy by developing new ways of promoting the role of women within nationalistic rhetoric. Beecher wrote prolifically on education and woman’s place in society, leading an American domestic science movement that was in tune with the demands of industrial capitalism of the late nineteenth century. Many women’s historians feel that Beecher’s influence devalued women’s labor regulating married women to the private sphere of the family household with out benefit of suffrage or property rights.

Catharine Beecher attended Sarah Pierce’s Lichtfield Female Academy from 1810 to 1816 first as a student and then as an assistant teacher. The Lichtfield Academy inculcated the philosophy of Republican Motherhood. This concept of gendered roles emerged during the Early Republican era when rhetoric espoused that the future of the nation was contingent upon women shaping and protecting the spiritual and moral life of society. When Miss Pierce’s nephew Charles Brace came to teach at the academy, he introduced a curriculum for boys along with Addisonian values of domestic gentility to female students. In this model, women and men shared intellectual equality in separate spheres: men conducted business and social activities in the public sphere and females managed the home and social obligations in the private sphere. The curriculum of the Litchfield Academy included reading, writing, composition, and English grammar; geography, ancient and modern history; philosophy and logic; spelling and simple needlework.

Raised in a Calvinist household, she studied music and drawing in preparation for a teaching career. She planned to marry a mariner, which meant that she would need an occupation while he was at see, her first opportunity to teach came in 1821 when she was hired to teach music and drawing in New London. Breaking with the Calvinist teachings of her father Lyman Beecher, Catharine settled into an acceptable occupation for a single woman which was teaching. Catharine wrote to her father on February 15, 1823, “there seems to be no very extensive sphere of usefulness for single woman but that which can be found in the limits of a schoolroom.” After the death of her fiancé Alexander Metcalf Fisher at sea in 1823, Catharine inherited a small fortune from his estate, which she and her sister Mary Foote Beecher used to establish a school for girls in Hartford, Connecticut. This school evolved into the Hartford Female Seminary. Mary did a bulk of the basic teaching, leaving Catharine time to develop her own teaching philosophy where academic excellence is fostered.

Holding a tiny doll that has a dress made by my mother. Photograph by R. I. Otterbach, 2014.

===

P.S. I have donned my folklorist attire to do some research on a French artist that settled in San Francisco in the 1910s after finding his name spelled in every which way on the Internet. I am having a blast with the old-fashioned gumshoe-ing and will report on findings in the coming weeks.