Flashback to March lock-down…

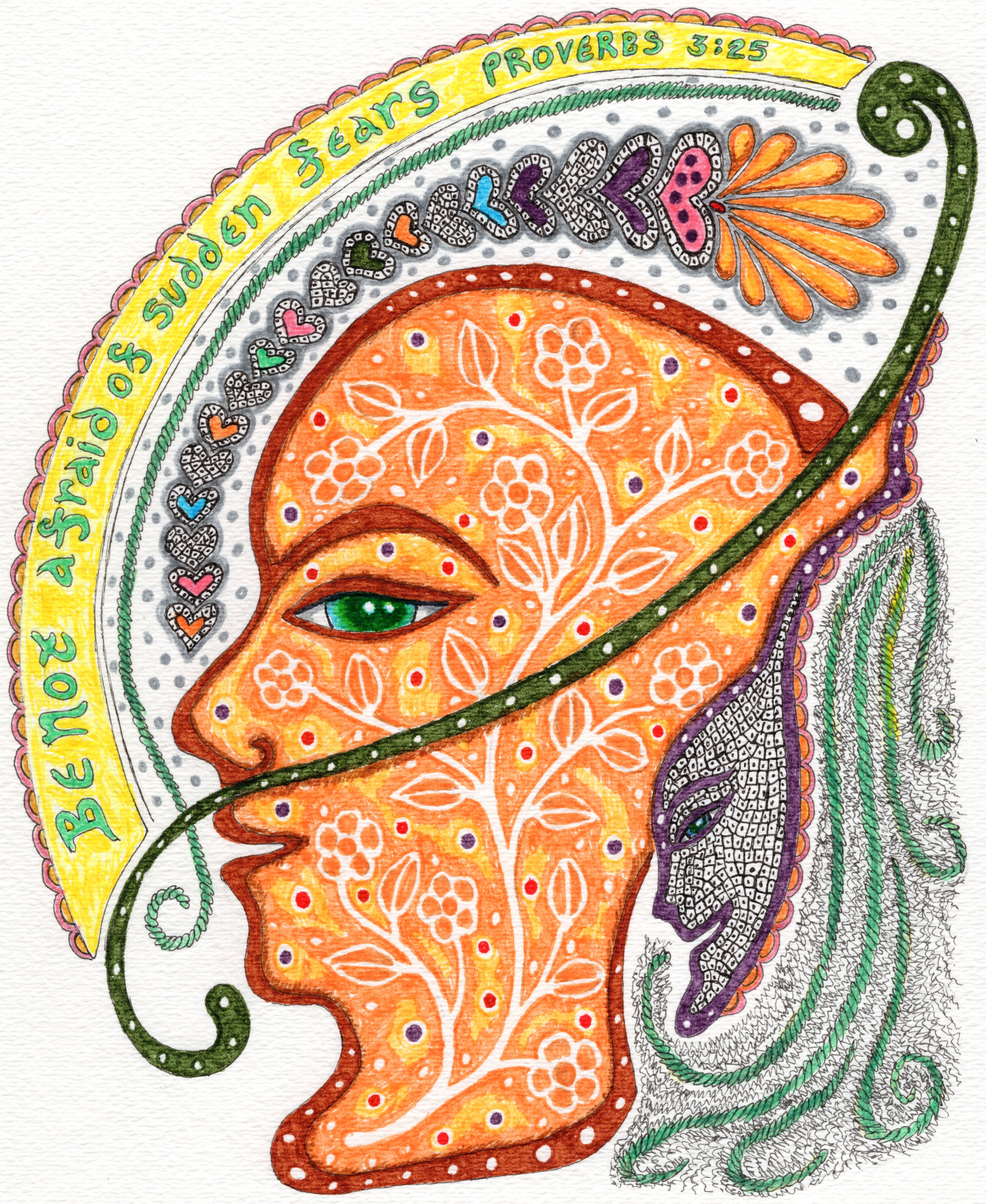

August 15, 2020

Doing History: Who tells it… who keeps it…

March 24, 2017

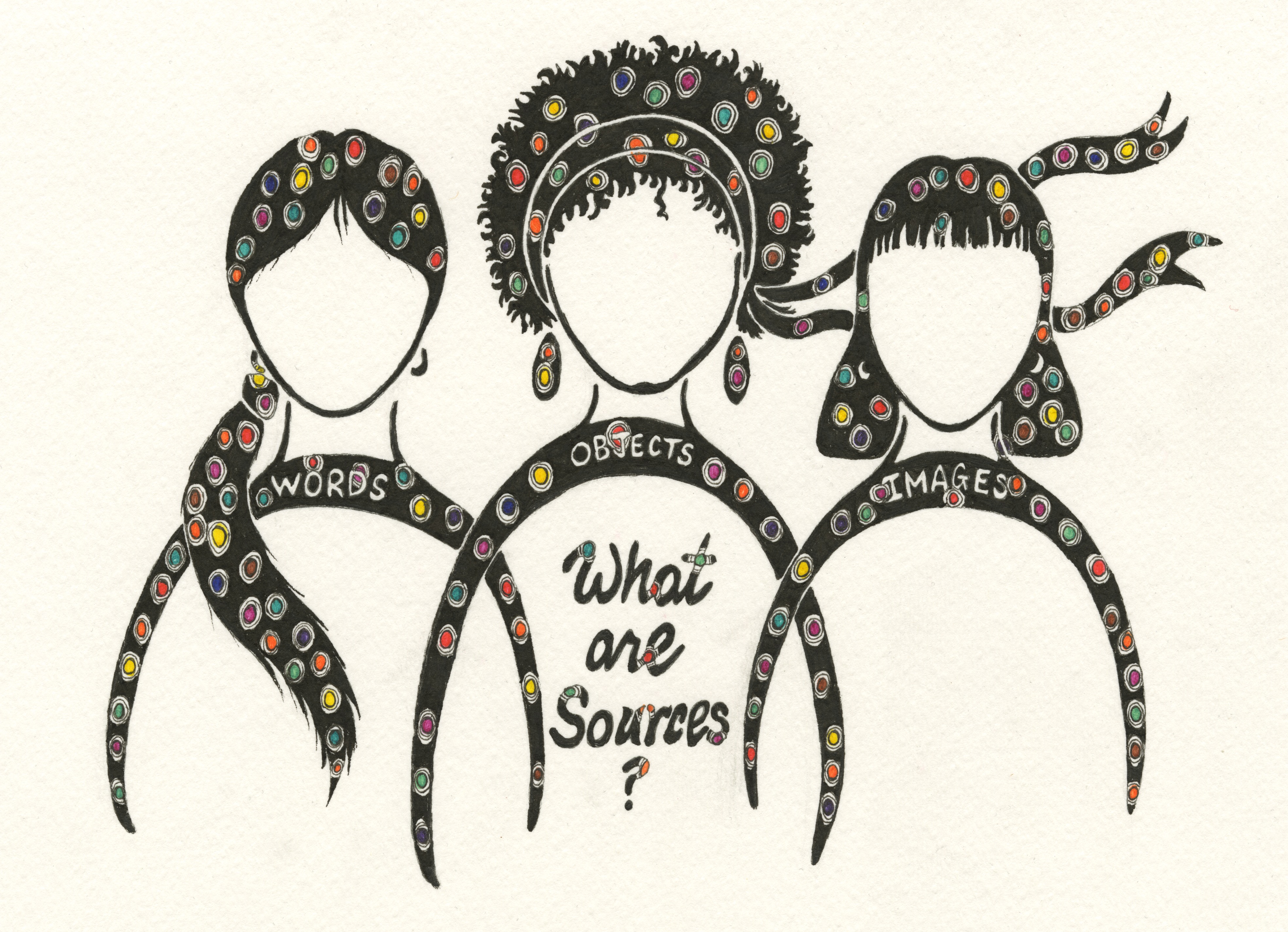

WHAT ARE SOURCES? WORDS – OBJECTS -IMAGES. Design by Meredith Eliassen, 2017.

What is re-search?

Doing research is the process of investigating evidence from the past; it can also involved surfacing and examining memories of individuals who resonate with our own values… or challenge them. Re-searching can be a valuable and transformative experience that compels us to check our own pulse and to be accountable. Detachment allows us to watch events unfold so that we can understand how a community’s character developed. We cannot look at our own past in anger. Our motivation to research directs our energy; questions channeled only with anger do not reveal truth that heals. As a society, we are who we are, and what we are because of events that happened in the past, and understanding the past can help us to develop maps of social justice for the future.

Where to begin… what is essential

Always begin research with resources that are available. Secondary research materials contain interpretations of evidence can provide essential overviews. Once you have an overview of your topic, you can then go to primary sources: words… objects… images…

WORDS

It is tempting to rely upon moving images to understand how events unfold, but they rarely tell the entire story. When critically thinking about broadcast news content consider who tells history and who collects history. Research must be comparative; relevance continually shifts in a changing world. Adjacent communities may be operating with and reacting to similar challenges to our own.

OBJECTS

A reset, retracing experiences from the past… Values shape the development of society and culture, and these factors change over time. What we care about can change radically, dramatically, and irrevocably with a single event.

IMAGES

Images from button pins to posters to photographs place ideas and events into context.

“Power to the people” was a powerful symbol of Third World student activism during the late-1960s.

Is “Childness” and the “Child’s Landscape” at Risk?

October 13, 2016

A Presentation for the American Folklore Society & International Society Folk Narrative Research Conference sponsored by the Children’s Folklore Section and the Folklore & Education Section in Miami, Florida, October 2016.

Unfortunately I will not be able to deliver this paper in person, but share it here:

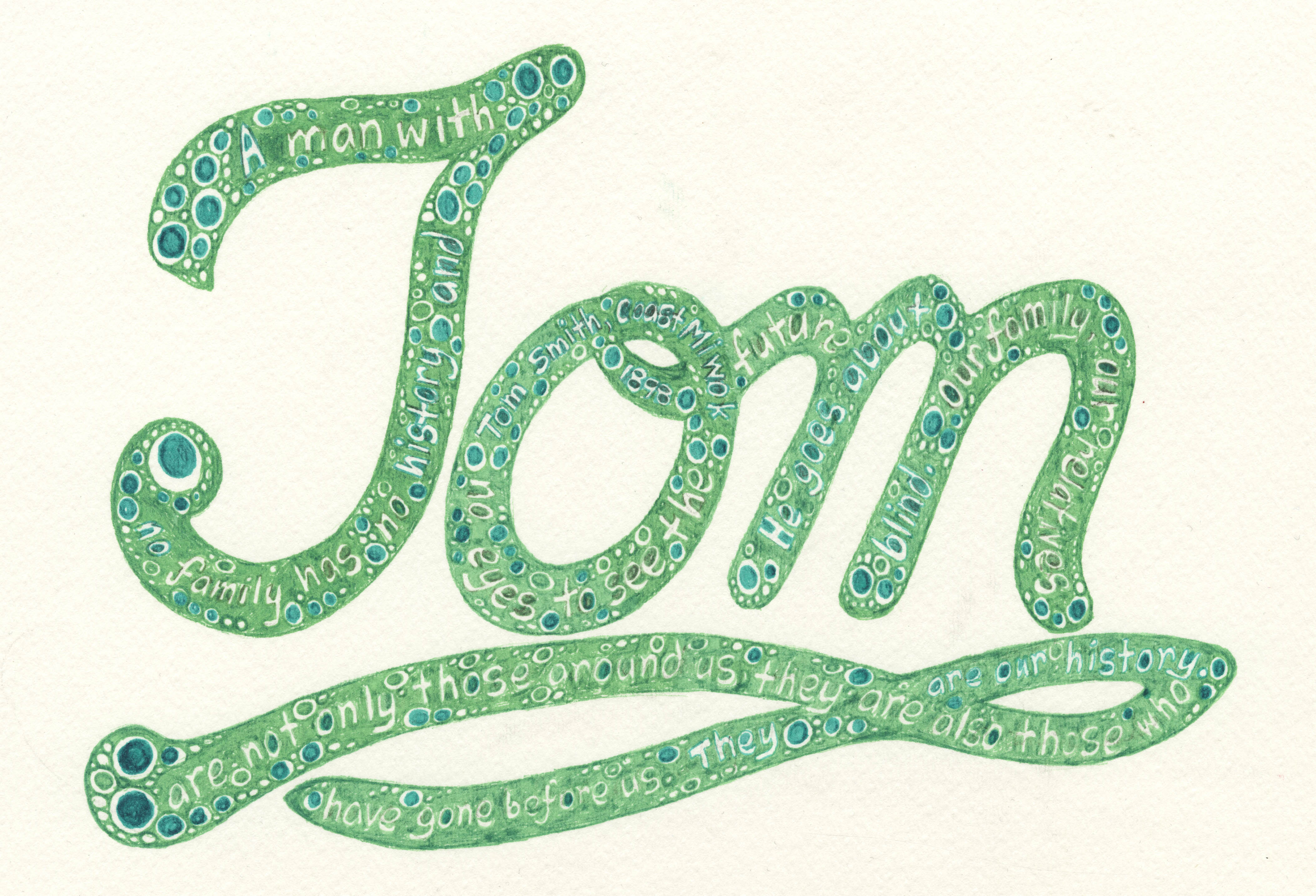

“A man with no family has no history and no eyes to see the future. He goes about blind. Our family, our relatives are not only those around us, they are also those who have gone before us. They are our history.” Tom Smith, Coast Miwok, 1898. Design by Meredith Eliassen, 2016.

What is childhood that we, as folklorists, need to study and chronicle its actual appearance? We understand it to be the time or condition of being a child. However, this understanding, our sensibility, our consciousness of childhood is in itself – ephemeral – as is childhood. The consciousness of childhood, is according to media ecologist Neil Postman, “a social artifact, not a biological category.”[1] A universal manifestation of this social artifact is curiosity – that ability of a young human to happily entertain himself or herself playing with an empty box or vessel once the novelty of the vessel’s contents has worn off, or to have the ability to create imaginary worlds with inanimate objects such as a twig, a stuffed animal, or an ordinary rag doll.[2] These inner workings of childhood as a human developmental stage and child culture with its quirky reflections of adult society are fodder for folklorists to chew and interpret. This presentation is informed by media ecology and considers how media has transformed the very nature of childhood over many generations at gateways to the future, as well as its implications today for children’s folklore and narratives that contain posterity’s unfinished stories.

If a folkway is defined as an actual way of thinking or behaving shared by members of a group as part of their common culture, then childhood is the folkway means for accessing common culture.[3] Children naturally explore, experiment, and create opportunities to test and expand boundaries within familial and societal contexts. Original play allows children to holistically experience events that involve a certain degree of risk and failure to provide opportunities to learn and develop knowledge and skills needed to survive as adults. For instance play jumping into and over puddles can test a child’s physical attributes as well as properties of the physical world. Likewise, childhood offers the potential to choose an actual vessel portal for imaginative play in order to explore its possibilities.

Historically events have occurred that interrupt, inform, and transform childhood. For instance, during the California Gold Rush (1848-1855), population sex ratios were dramatically skewed causing men to overly romanticize children and childhood in their absence. Conversely, the legalization of same-sex marriage within our lifetimes has prescribed an institutionalized shift in adult constructions of family and childhood that may or may not resonate with all common folk. Folklorist, however, must also consider today’s child within a dominant adult-designs, consumer-driven context. Here, definitions of childhood differ: Postman, in the late-twentieth century, delineated the period of modern childhood to exist from the age of seven to seventeen years, coinciding approximately with school years.[4] Today it could be argued that childhood has increasingly extended into adulthood.

Likewise, technological innovations have historically interrupted, informed, and transformed childhood.[5] Media ecology examines how communication media affect human perception, understanding, feeling, and value. A medium can encompasses complex message systems that impose certain ways and paths for thinking, feeling, and behaving. However, media ecology goes further; it asks how our interactions with media help or hinder our shared human chances for survival.

Marshall McLuhan asserted that three inventions were vectors for successive social transformation: the written phonetic alphabet carried humans from tribal to literate society; the printing press carried humans from literate to print society; and the telegraph carried humans from print to today’s increasingly electronic society by progressively arousing different brain patterns over generations that are distinctive to each particular form of dominant communication. For instance, we take for granted that humans could always perceive color as we perceive it today, but advances in communications and the manufacturing of material objects over centuries has altered our color perception.[6]

During the Tribal Age, the primordial medium for mass communication was speech: the ear was the dominant receptive sense organ, and therefore, hearing, touch, taste, and smell became more strongly developed in humans than sight. In the Bible, readers are introduced to the ancient tribal child named Samuel who exemplified this auditory sense that seemed to cross cultural boundaries (I Samuel 3: 1:11). Here, “consciousness,” can be defined, as awareness or perception of an inward spiritual or psychological fact, or, an inward awareness of an external object, state, or fact.

When we think of childhood, we think of a period where play is connected with social immersion; the common definition for play in this sense suggests taking on or pretending to be in an adult role. In the time of the Ancients, children played clapping games that incorporated the most fundamental human sensory toy – human hands –required no external equipment. Dolls and other inanimate objects, conversely, were introduced, and became more complex and paradoxical media external extensions of the child’s being, where subtle issues of parent-child control came into being.

We cannot underestimate the significance of new media on young children. Historically, Native Americans on the West Coast used baskets as if they are extensions of the human body; infants got immersed in water-holding baskets as they got immersed in culture. Native American basket engineers were media ethno botanists who manufactured amplified baskets from spiritualized raw natural materials. Here we sense the concept of ecology as the study of environment and how its structure and content impact human beings: when the United States government attempted to eradicate the tribes in southern Oregon, they destroyed functional Native American baskets as a war tactic.[7]

During the Literary Age (or visual era), the eyes became the dominant sense organ. Media ecologist Walter J. Ong, in distinguishing orality by examining thought and its verbal expressions within illiterate populations, illuminated a monumental shift from a world of sound to a world of vision that emerged with the printed word. According to Ong, scribing was not just an appendage to speech, it moved speech from an oral world into a new sensory world – that of vision –subsequently transforming speech and thought. Ong concluded, “Notches on sticks and other aides-memoire lead up to writing, but they do not restructure the human life-world as true writing does.”[8] Yet, even though the ancient media of speech and song were radically reconfigured with the introduction of the new media of reading and writing, they were never supplanted.[9]

The translation of sounds into letters and new visible symbolic objects radically altered the human consciousness: words could be read repeatedly and when individuals became literate, they could build upon recorded knowledge and advance thinking. When Aldus Manutius (1449-1515) began to mass-produce pocket-sized texts featuring italic type in 1502, this technology allowed humans to easily transport and share ideas. Media ecologists concur that with the print age, a consciousness of childhood as a distinct period of human development first emerged with a moral chiaroscuro of print media where the semantics of childhood was delineated by adult societal constructs of parenthood.[10] This change was monumental enough to be reflected architecturally with the development of the study as a distinct space where heads of noble households could seek privacy and isolation from dependents that included women, children, and servants in order to read adult material.

As the Industrial Revolution later unfolded, common folk fathers left the immediate household in order to find work and families relocated to urban areas where there was less child-care support from extended families.[11] At this time folklore (simple and unpretentious conversations of common people) was relegated and domesticated into literature for women and children’s literature. Girls were consequently allowed to become literate enough to take on the role of motherhood and were expected to guide and discipline children on a daily basis. Women’s literature in the mid-nineteenth century increasingly prescribed child-rearing advice to women utilizing contemporary media that separated women from folkways.

The Electronic Age, heralded by Samuel Morse’s invention of the telegraph that led to the telephone, the cell phone, television, internet, and so on, brought about an era of instant communication and an eventual return to an environment with simultaneous sounds and touch.[12] Having the ability to be in constant contact with the world has created what McLuhan termed, a “global village.”[13] The invention of the telegraph coincided with the work of German educator, Frederick Froebel (1782-1852), who revolutionized early education when he demonstrated that young children were capable of rapid skill acquisition when they were allowed to use play media that exploited their affinity towards active play.

Play, for Froebel was the highest expression of human development in childhood that allowed for the free expression of the child’s soul.[14] Although Froebel focused on specific games and activities using balls and shapes, he felt that all toys should be suited to the particular intellectual demands of children at specific ages; the sophistication of the toy or doll was designed to match that of the child.[15]

In 1896 pioneering American psychologist G. Stanley Hall (1846-1924) and Caswell Ellis (1871-1948) published a survey focused on how children played and interacted psychologically with dolls. The Ellis and Hall found that doll passion was strongest for children between the seven and ten years of age, reaching its climax between eight and nine. Ellis and Hall asserted: “Whispered confidences with the doll are often more intimate and sacred than with any human being. The doll is taught those things learned best or in which the child has most interest.”[16] During doll play, girls make and control the rules for play, and in turn the dolls provided girls with freedom for self-expression.

In Conclusion

In the twenty-first century we may well ask, are childhood and the child’s landscape, as we have known them at risk? Postman asserted in the late-twentieth century that, “… children themselves, are a force in preserving childhood.”[17] However, interactive media for child’s play and entertainment media devices (like dolls or balls) have become an extension of the child’s arm and hand. When mass-produced toys create total-entertainment-experiences, society can loose ecosystems where holistic inner-imaginary landscapes flourish. Although folklorists will adapt to this technologist for studying First World childhood, we may need to head for the Cloud[s] to find our fodder for studying. Media ecology surfaces roles that media compel us to play. Media ecology will continue to spotlight how emerging media structures the semantics of what we see and how media informs how we feel and act as we approach the gateway to the future with our eyes, ears, and hands wide open.

Sources used:

Barius, Annie Howes. 1895. “The History of a Child’s Passion.” The Woman’s Anthropological Society Bulletin, online: https://archive.org/details/101161943.nlm.nih.gov

Deutscher, Guy. 2010. Through the Language Glass: Why the World Looks Different in other Languages. New York: Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt and Company.

Ellis, A. Caswell, and G. Stanley Hall. “A Study of Dolls.” Pedagogical Seminary. Vol. 1:2 (December 1896): 129-175.

Froebel, Friedrich, translated by Josephine Jarvis. 1896. Pedagogies of the Kindergarten, or, His Ideas Concerning Play and Playthings of the Child. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

Gopnik, Alison. 2016. The Gardner and the Carpenter: What the New Science of Child Development Tells Us About the Relationship Between Parents and Children. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Hanscom, Angela J. 2016. Balanced and Barefoot: How Unrestricted Outdoor Play Makes for Strong, Confident, and Capable Children. Oakland, CA.: New Harbinger Publications.

Johnson, Samuel. 1785. A Dictionary of the English language: in which the words are deduced from their originals, and illustrated in their different significations by examples from the best writers. To which are prefixed, a history of the language, and an English grammar. In two volumes. London: J. F. and C. Rivington.

McLuhan, Marshall, Quentin Fiore, and Jerome Agel. 1967. The medium is the massage. New York: Bantam Books.

Ong, Walter J. 2002. Orality and literacy: the Technologizing of the Word. London: Psychology Press.

Postman, Neil. 1982. Disappearance of Childhood. New York: Delacorte Press.

Thornton, Dora. 1997. The Scholar in his study: Ownership and Experience in Renaissance Italy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Endnotes:

[1] The common definition of childhood is “the time and condition of being a child.” This paper is informed by a conversation of childhood among three media ecologists: Marshall McLuhan (1911-1980), Rev. Walther J. Ong (1912-2003), and Neil Postman (1931-2003). Neil Postman, Neil, The Disappearance of Childhood (New York: Vintage Books, 1994), xi.

[2] Child culture has to some extent always been an adult societal construct since children are dependent upon adults as this stage. This paper asserts a difference between virtual and imaginary in connection to childhood: virtual means existing in effect or for practical reasons though not in real fact or form and imaginary refers to mental pictures or imagery derived from an ability of the human mind to conceive ideas or to form images of something not actually present; the power of mental conception.

[3] The concept of “conversation,” as the action of living or dwelling, associating or having dealings with others, or conduct and behavior, has evolved.

[4] Postman, 1982, 85.

[5] A medium or technology can shape the form and semantics of a culture’s politics, social organization, and common ways of thinking, and the interaction between human beings and media gives meaning and symbolic balance to that culture.

[6] Guy Deutcher asserts, “a nation’s language, so we are often told, reflects its culture, psyche, and modes of thought,” in his Through the Language Glass: Why the World Looks Different in other Languages (New York: Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt and Company, 2010), 1. Scholars have come to believe that color perception is evolving and that perhaps, the world saw in black and white until a human consciousness reached for the perception of additional colors over many generations as pigments began to be manufactured; that our ancestors could see first black and white, followed by red, yellow, green and then blue. Ibid., 58-63.

[7] In southern Oregon, during the Rogue River Indian War (1855-1856), vigilantes and army troops attacked Tututni villages employing a military tactic to undermine tribal stability by destroying all baskets and their contents that were use in every aspect of life, because without baskets, the tribes were unable to survive. Stephen Dow Beckham, Requiem for a People: The Rogue Indians and the Frontiersmen (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971), 27.

[8] Walter J. Ong, Orality and literacy: The Technologizing of the Word (London: Psychology Press, 2002), 85.

[9] Alison Gopnik, The Gardner and the Carpenter: What the New Science of Child Development Tells Us About the Relationship Between Parents and Children (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016), 221.

[10] Pietro Aretino (1492 -1556) was an Italian author, playwright, poet, satirist and blackmailer who wielded immense influence on contemporary art and politics and invented modern pornographic literature. The ideal of childhood emerged out of the Renaissance (Postman, 1994, xi). During the Renaissance, childhood coincided with the emergence of the scholar’s study as a distinct architectural component of the household as an office or writing room where the adult head of household (usually a man) could retreat/retire from the rest of the household for private reflection and solitude. Dora Thornton the space known as “the study” as not only a distinct architectural innovation, but as a medium with its own instruments and a “virtuous space of unique moral and aesthetic worth in her book, The Scholar in his Study: Ownership and Experience in Renaissance Italy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 176.

[11] Sarah Fielding’s The Governess, or, The Little Female Academy was published in 1749. This is the first novel written for adolescent girls, and Fielding modeled it after John Locke’s work and it contained fable and fairy tales that taught moral lessons. In the midst of the European Industrial Revolution, lexicographer Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) defined childhood to be, “1. The state of children; or, the time in which we are children: it includes infancy, but is continued to puberty; 2. The time of life between infancy and puberty; 3. The properties of a child.” Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English language: in which the words are deduced from their originals, and illustrated in their different significations by examples from the best writers. To which are prefixed, a history of the language, and an English grammar. In two volumes (London: J. F. and C. Rivington, 1785), 1: CHI.

[12] Childhood, according to Postman, emerged in the United States in about 1832, Postman, 1982, xi.

[13] Marshall McLuhan “The youth of today are not permitted to approach the traditional heritage of mankind through the door of technological awareness. This only possible door for them is slammed in their faces by a rear-view-mirror society.” From McLuhan, Quentin Fiore, and Jerome Agel. 1967. The Medium is the Massage (New York: Bantam Books, 1967), 100. Eric McLuhan (1996). “The source of the term ‘global village'”. McLuhan Studies (issue 2). Retrieved 2016-9-3.

[14] “For we see the whole inner spiritual life of the child manifest the threefold phenomenon, spontaneous activity, habit, and imitation, as a triune phenomenon.” Froebel is translated by Josephine Jarvis. 1896. Pedagogies of the Kindergarten, or, His Ideas Concerning Play and Playthings of the Child (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1896), 28.

[15] Froebel’s pedagogy for young children was based upon the sensibility that child is a spiritual being. “These aims are, to keep itself such as it feels and finds itself – a being which is independent and yet supported by the whole; to strengthen, exercise, and develop its limbs and senses, and to make them free, thus within itself and by its own efforts to attain more and more independence and personality, and to reveal to itself in its personality; finally to obtain knowledge of the independence and personality – that is of independent existence – of that which surrounds it, and to convince itself of that existence.“ Froebel, 1896, 28-29. Occupational therapist Angela J. Hanscom has observed in her practice that children (including toddlers) are requiring occupational therapy services to deal with challenges of balance, motor skills, and other attention and emotional challenges; she asserts that with unrestricted play, “Children will naturally create their own rules and set their own boundaries,” and “Kids determine when to stop on their own – when they feel done.” Hanscom, Balanced and Barefoot: How Unrestricted Outdoor Play Makes for Strong, Confident, and Capable Children. Oakland, CA.: New Harbinger Publications, 2016), 71-22.

[16] A. Caswell Ellis and G. Stanley Hall conducted a survey of based upon informal examination of children from many different ages that was circulated as a questionnaire among eight hundred teachers and parents. The survey focused on the types of dolls that children preferred, how they played and interacted psychologically with dolls, and doll/child rituals such as naming, feeding, discipline, sleep, hygiene, sickness and death and the doll’s social life. The results were published in “A Study of Dolls.” Pedagogical Seminary. Vol. 1:2 (December 1896): 129-175. They continue this theme: “The little mother’s real ideas of morality are best seen in her punishments and rewards of her doll. Her favorite foods are those of her doll. The features of funerals, weddings, schools, and parties, which are re-enacted with the doll, are those, which have most deeply impressed the child. The child’s moods, ideals of life, dress, etc., come to utterance in free and spontaneous doll play (Ellis and Hall, 1896, 162-3)”. Froebel asserts: “The outermost point and innermost ground of all phenomena of the earliest life and activity of the child is this: the child must bring into exercise the dim anticipation of conscious life in itself as well as of life around it; the consequently must exercise power, test and thus compare power, exercise independence, and test and thus compare the degree of independence (Froebel, 1896, 31)”.

[17] Postman, 1994, viii. “Many of our institutions suppress all the natural direct experience of youth, who respond with untaught delight to the poetry and the beauty of the new technological environment, the environment of popular culture McLuhan, 1967, 100.” However, since that time fundamental changes in children’s play spaces have occurred. Children have less unrestricted play in the 21st century, and playground equipment have become less physically challenging and has been move indoors, according to Hanscom, 2016, 133-151. Hanscom observes, “…by constantly rushing children, restricting their movement, and diminishing their time to play, we are causing them more harm than good (Ibid., 60).”

Natural childhood? or marketed childhood…

September 21, 2016

“Brother Buzz” design by Meredith Eliassen, 2016.

The Latham Foundation to promote Humane Education was established in 1918 to foster in children a better understanding of the importance of treating animals well. The character of Brother Buzz (an elf in the form of a bee) was created to appeal to children and teach them about animals. Brother Buzz appeared first in print form in 1927, then on radio in the 1930s during the Great Depression, and then local television as World War II veterans opened up the broadcasting industry. The Wonderful World of Brother Buzz (1952-1969) was the longest running locally produced children’s program in the San Francisco Bay Area and the first to feature a puppet promoting the humane treatment of animals.

American pediatrician Benjamin Spock (1903-1998) revolutionized child rearing and childhood with his book Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care (1946) that promoted a kind of permissive parenting when it asserted to mothers, ”You know more than you think you know.” Spock brought about major social change in childhood as young mothers in the post-war years relied more upon his marketed advice than upon family advice. American psycho-historian Lloyd deMause in examining the overarching psychological motivations of childhood through history found that Spock was part of a movement that asserted that the child “knows better than the parent what it needs at each stage in life.” While this perhaps gave parents the opportunity for nostalgic visits to childhood through their children, and the opportunity for children to be more independent to express views, it also subverted traditional safety boundaries. It would also bring in huge profits for baby and children’s stores lasting from approximately 1948 until 1970 when the baby bust occurred.

The Ancients and Media Ecology

September 12, 2016

Child culture has to some extent always been an adult societal construct since children are dependent upon adults as this stage. Lydia Maria Child, 1802-1880 wrote in the preface of her The Mother’s Book (1832): “We are told that when Antipater demanded of the Lacedemonians fifty of their children as hostages, they replied that they would rather surrender fifty of the most eminent men in the state, whose principles were already formed, than children to whom the want of early instruction would be a loss altogether irreparable (vii).”

Marshall McLuhan (1911-1980) asserted that three inventions were vectors for successive social transformation: the written phonetic alphabet carried humans from tribal to literate society; the printing press carried humans from literate to print society; and the telegraph carried humans from print to today’s increasingly electronic society by progressively arousing different brain patterns over generations that are distinctive to each particular form of dominant communication.

Plato… on writing, in “Phaedrus”: ‘If men learn this, it will implant forgetfulness in their souls… they will cease to exercise memory because they will rely on that which is written, calling things to remembrance no longer from within themselves, but by means of external marks.’ Design by Meredith Eliassen, 2016.

In the medieval world, there was no separate sphere for children; adults and the young had access to all common conversations that were part of the culture; a seven year old boy only differed from his father in his capacity to engage in love and war. The translation of sounds into letters and new visible symbolic objects radically altered the human consciousness: words could be read repeatedly and when individuals became literate, they could build upon recorded knowledge and advance thinking. When Aldus Manutius (1449-1515) began to mass-produce pocket-sized texts featuring italic type in 1502, this technology allowed humans to easily transport and share ideas. Media ecologists concur that with the print age, a consciousness of childhood as a distinct period of human development first emerged with a moral chiaroscuro of print media where the semantics of childhood was delineated by adult societal constructs of parenthood.

Aldus Manutius (1449-1515) established his printing house in Venice in about 1490. The Aldine Press was a corporate entity; the entrance placard conveyed the proprietor’s eithic: “Talk of nothing but business; and dispatch that business quickly.” Pietro Aretino (1492 -1556) was an Italian author, playwright, poet, satirist and blackmailer who wielded immense influence on contemporary art and politics and developed early pornographic literature. He wrote “We are the buffoons of our children.” Design by Meredith Eliassen, 2016.

Giovanni Francesco Straparola, approximately 1460-1557 (roughly translates to “The Babbler”) is credited with having introduced the genre of fairy tale, including “The Puss in Boots,” into contemporary European literature. He published a collection of popular stories incorporating practical jokes, romances, and fables in the style of the Decameron in Venice in 1550. It passed through sixteen editions in twenty years and was translated into French and German. The frame story is that Francesca Gonzaga, daughter of Ottaviano Sforza, Duke of Milan, escapes the commotions in that city and retires to the island of Murano, near Venice, where surrounded by a number of distinguished ladies and gentlemen, she passes the time in listening to stories related by the company. Thirteen nights are spent in this way, and seventy-four stories are told, when the approach of Lent cuts short the diversion. These stories are of the most varied form and origin and many are borrowed without acknowledgment from other writers including Morlini, Boccaccio, and others. Twenty-nine of the tales are from Straparola; they had never appeared before in European literature, but they were in no sense original to Straparola. His work had no influence on contemporary Italian literature (and was actually banned in areas), and was soon forgotten.

Learn more about media ecologists from the Media Ecologist Association.

Childhood at Risk? A Folklorist Investigates

September 10, 2016

“I can write my name but I can’t spell the letters.” Words by Joseph Simas, “Kinderpart,” 1989, design by Meredith Eliassen, 2016.

If a folkway is defined as a way of thinking or acting shared by members of a group as part of their common culture, then childhood is the means for accessing common culture. Children are vectors of imaginary landscapes within adult societal constructs. Children naturally explore, experiment, and create opportunities to test and expand boundaries within familial and community contexts. Original play allows children to holistically experience events that involve a certain degree of risk and failure to provide opportunities to learn and develop knowledge and skills needed to survive as adults engaged with society. For instance play jumping into and over puddles can test a child’s physical attributes as well as properties of the physical world. Likewise, childhood offers the potential to choose a simple vessel portal for imaginative play in order to explore its possibilities.

“Media as an extension of the human hand,” conceptual drawing by Meredith Eliassen, 2016

The cell phone can now be an interactive medium for child’s play and entertainment in an increasingly secular world. As folklorist, we can see with the lens of media ecology that this little device (like a play doll or ball of earlier days) has become an extension of the child or teenager’s arm and hand. Therefore, we can ask as with other media:

- Does this device structure what we can see and say and, therefore, do?

- Does this device assign to us roles to play? And then insist upon our playing them?

- Does this “smart” device explicitly specify what we are permitted to do and what we cannot do?

- Does this device offer half-concealed implicit and informal specifications that compel us assumption that what we are dealing with merely a machine and not a highly-corporate media environment?

When mass-produced toys create total-entertainment-experiences, society can loose ecosystems where holistic inner-imaginary landscapes flourish. Although folklorists will adapt to this technologist for studying First World childhood, we may need to head for the Cloud[s] to find our fodder for studying the real or ordinary lives of children. Media ecology surfaces roles that media compel us to play. Media ecology will continue to spotlight how emerging media structures the semantics of what we see and how media informs how we feel and act as we approach the gateway to the future with our eyes, ears, and hands wide open. In the coming weeks, I will explore the transitions of earlier media in this blog to identify areas that might be considered when asking the question: Is childhood at risk?

Here is a recent article from the Washington Post: And everyone saw it… by Jessica Contrera

To learn more about media ecologist go to the Media Ecologist Association.

Angelou on the Semantics of Education

August 30, 2016

“Education is man’s most amazing tool… amazing toy, or effective tool, or it can be… man’s most effective weapon. Education” Maya Angelou “Blacks, Blues, Black!,” 1968. Design by Meredith Eliassen

“Blacks, Blues, Black!” (Episode 6: Education)

Conversely, Native Americans in California used baskets as if they are extensions of the human body; infants were immersed in water-holding baskets as they get immersed in culture. Basket makers are engineers who create amplified baskets from spiritualized raw natural materials; as children learned gendered tasks related to basket and net making, they learned cultural values. Here we perceive the concept of ecology as the study of environment and how its structure and content impact human beings. When the United States government attempted to eradicate the tribes in southern Oregon, they destroyed functional Native American baskets as a war tactic. In southern Oregon, during the Rogue River Indian War (1855-1856), vigilantes and army troops attacked Tututni villages employing a military tactic to undermine tribal stability by destroying all baskets and their contents that were use in every aspect of life, because without baskets, the tribes were unable to survive (See note).

In medieval European England, Biblical translator and reformer John Wycliffe (1338-1384) came to regard the scriptures as the only reliable guide to the Truth that came from God. Wycliffe maintained that all Christians should rely on the Bible rather than on the teachings of popes and clerics. He said that there was no scriptural justification for the papacy. In keeping with Wycliffe’s belief that scripture was the only authoritative reliable guide to living a good life, he became involved in efforts to translate the Bible into English as a means of empowering the common folk. Wycliffe asserted that not having English-language Bibles meant that it was not accessible to laypeople, therefore the common people were being deprived of God’s Word because it was written in the language of a foreign people.

Note: Stephen Dow Beckham, Requiem for a People: The Rogue Indians and the Frontiersmen (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971), 27.

A Toddler named Alma, on the sky…

August 29, 2016

British politician and orator William Gladstone (1809-1898) studied The Iliad and The Odyssey by the Greek writer Homer who was active during the eighth century BC, and came to the conclusion that Homer must have been colorblind. However more recently, scholars have come to believe that color perception must be evolving and that perhaps, the world saw in black and white until a human consciousness reached for the perception of additional colors over many generations; that our ancestors could see first black and white, followed by red, yellow, green and then blue.

Consider “boo” for blue… is the sky blue? Alma responds, “Blue, eh no, white, um no blue…” Design by Meredith, 2016.

My friend Ella turned me on to this program by Radio Lab…

Radio Lab: Why Isn’t the Sky Blue? http://www.radiolab.org/story/211213-sky-isnt-blue/ Radiolab is a show about curiosity. Where sound illuminates ideas, and the boundaries blur between science, philosophy, and human experience.

The program asserted that colors entered the human consciousness as they were manufactured, and the earliest manufactured blue pigment was created in ancient Egypt.

Some ancient beads from Egypt.

Media Ecology: Introduction

August 26, 2016

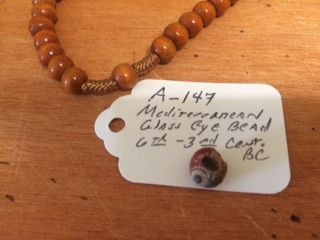

Beads are an ancient medium for communication.

The earliest beads were produced in tubular, barrel, or disc-shaped forms; they were manufactured with technology and raw materials available. Once the technology was developed to make spherical beads, they dominated; though in many cultures, the earlier designs were never superseded. However, the sphere shaped bead was recognized as a small portable sculpture… whole and perfect… they could be joined together to form a circlet of, say, prayer beads, whereby the beads collectively became a primal extension of the human hand and consciousness. Thus, beads as an inanimate vessel medium that humans could be imbued with spiritual semantic with which to build human-object relationships.

A photograph of a small Mediterranean glass eye bead (circa 6th – 3rd century B.C.) and modern prayer beads.

Introducing a new “eye bead” motif to this blog…

Disiderius Erasmus (c. 1466-1536) “In region caecorum rex est luscus = In the country of the blind, the one-eyed man is king.” ~ circa 1500. Design by Meredith Eliassen, 2016.

Disiderius Erasmus (c. 1466-1536) was a Dutch scholar considered by many to be the greatest humanist of the Renaissance era. At a time when children were thought to be unformed adults, Erasmus perceived them to be little “barbarians” in need of civilizing. He identified childhood as a period when children need different forms of dress from adults to fit function. In establishing a concept of adulthood, Erasmus was also credited with establishing the concept of childhood as discerned a distinct period of development when book learning during childhood was needed as part a the civilizing process needed to conquer animal behavior in humans.

The Web of Childhood: Media Ecology and Dolls

February 1, 2016

Dolls are complex and paradoxical toys where subtle issues of parent-child control can come into play. Parents and children had different motives for employing dolls – parents wanted girls to play with dolls for instruction and socialization, and children played with dolls because they were fun. Dolls were used to teach American girls lessons in domesticity, specifically needle-crafts such as sewing and knitting, that were necessary to maintain home economy. In an ephemeral way, dolls before the advent of electronic devices could become an extension of the child’s very being.

“We wove a web in childhood, a web of sunny air.” Quote by Charlotte Brontë (1816-1855), drawing by Meredith Eliassen, 2016.

Prior to the Victorian era, historians agree that doll play for boys and girls was a means for creating inner-landscapes where “problems of being” could be resolved with play. During the early-nineteenth century, German educator, Frederick Froebel (1782-1852) revolutionized early education, when he showed that young children were capable of rapid skill acquisition when they were allowed to use materials that employed their tendency towards active play as they developed their minds. Although Froebel focused on specific games and activities using balls and shapes, he felt that all toys should be suited to the particular intellectual demands of children at specific ages. Thus, the sophistication of the toy or doll was designed to match that of the child. Froebel said: “Play, then, is the highest expression of human development in childhood, for it alone is the free expression of the child’s soul. It is the purest and most spiritual product of the child, and at the same time it is a type and copy of human life at all stages and in all relations.”

With the influence of Queen Victoria (1819-1901), a dichotomy emerged where dolls became the exclusive domain of girls. Queen Victoria was significant in expanding the educational functions of dolls in the nursery. Even before her reign, Princess Victoria collected wood dolls — and with guidance from her governess — she sewed clothing for her dolls until she was about fourteen years old. The Princess’s portrait dolls represented people in the court and famous personalities of her time. These dolls served an additional function beyond being toys; they documented social history in the Royal Household. This use of dolls in socializing girls quickly spread from England to America and remained popular.

Karin Calvert asserted in her book, Children in the House (1992), that parents wanted their children to conform to very distinct and rigid social roles existing for men and women. Boys should “take” their pleasure with active play while girls “busied” themselves by imitating women’s domestic duties. In studying the educational functions of the doll, one must begin by examining gender roles that required girls to need such careful training to be good wives and mothers. Economic and social changes related to the Industrial Age dramatically impacted family life. Not only did fathers leave the immediate household in order to find work, but families also moved to urban areas where there was less child-care support from extended families. For this very reason, women’s literature during the mid-nineteenth century filled a void for women by providing child-rearing advice. Mothers were expected to guide and discipline children on a daily basis, using a combination of love, reason, approbation, and rewards. The Victorian concept of the ideal mother — a woman always available and always loving — was prescribed in women’s literature. She was strict but loving, ever affectionate with her brood, and always successful in commanding absolute obedience from her children. Popular culture exalted the role of mothers, and mothers served as the emotional center of domestic life.

While sewing and textile production was traditionally important to domestic economy along with dairying, food preparation, housekeeping and child care, its importance seemed to increase during the Victorian era. Women sometimes utilized these skills as an occupation to supplement family incomes, but they were seldom able to earn enough to live independent lives. In 1837, Eliza Farrar (1791-1870) commented in the Young Lady’s Friend: “A woman who does not know how to sew is as deficient in her education as a man who cannot write.”

In 1843, Lydia Maria Child (1802-1880), in her classic work, the Little Girl’s Own Book, gave basic instructions for plain sewing, mending, knitting, along with patterns for competing simple projects. She said: “There is no accomplishment of any kind more desirable for a woman, than neatness and skill in the use of a needle. To some, it is an employment not only useful, but absolutely necessary; and it furnishes a tasteful amusement to all. The first and most important branch, is plain sewing. Every little girl, before she is twelve years old should know how to cut and make a shirt with perfect accuracy and neatness. Child also commented that: “At infant schools in England, children of three and four years old make miniature shirts, about big enough for a large doll.”

A girl’s education in sewing occurred at home — she was instructed by her mother, older females in the household, or older friends. However, as a young girl, her education could be self-directed if she had a doll to care for. Children’s magazines such as St. Nicholas, included articles for children with instructions for sewing or knitting, along with doll stories that contained basic instructions for creating doll clothes. Some articles included patterns, but many children had to copy illustrations from books and magazines in order create their own patterns. In the process, they learned all aspects of dressmaking and basic tailoring. “Child included a selection in her book called, “Dolls”: “The dressing of dolls is a useful as well as a pleasant employment for little girls. If they are careful about small gowns, caps, and spencers, it will tend to make them ingenious about their own dresses, when they are older. I once knew a little girl who had twelve dolls; some of them were given to her; but the greater part she herself made from rags, and her older sister painted their lips and eyes. She took it into her head that she would dress the dolls in the costumes of different nations. No one assisted, but by looking in a book called Manners and Customs, she dressed them all with great taste and propriety… I assure you they were an extremely pretty sight. The best thing of all was the sewing was done with the most perfect neatness. When little girls are alone, dolls may serve for company. They can be scolded and advised, and kissed, and taught to read, and sung to sleep — and anything else the fancy of the owner may devise.

In 1848, Mrs. Helen C. Knight actually opposed sending girls to school. She commented in the Mother’s Assistant: The sphere of the female is at home; and an ignorance of her duties there, brings discredit and unhappiness to herself, and discomfort and sorrow to her family. When is the best season for learning these duties? It must be in youth; they must form a portion of every day’s striving and learning; they must be nourished in our daily habits. It is the child which must be taught to take care of its chamber and its drawers, to bear and forbear with its little brother, to come in with its young energies to the help of mother, and to feel the importance of sewing in the manufacture of its own garments.

American textbooks from the Victorian period document gender roles of the time in their texts and illustrations. More than learning to read, children were being educated to take their place in society. McGuffey Eclectic Readers were the most widely distributed school-books in America from 1836 until 1910. Although the McGuffey Eclectic Readers were criticized for being didactic and moralistic, this series is considered by many to be an important force in shaping the consciousness of Middle America. While early editions contain few references to dolls, revisions of the Eclectic Readers contained passages where dolls teach moral lessons about sharing and caring for possessions.

McGuffey’s Second Eclectic Reader contains a lesson called, “The Torn Doll,” where young Mary Armstrong learns the importance of taking proper care of her doll. One day while Mary is playing in the yard, she abandons her favorite doll on the porch where the family dog, named Dash can find it. Dash grabs the doll and roughly plays with it, and tears it. The next morning when Mary finds her broken doll, she harshly scolds the dog. Her mother comes to the dog’s defense and says, “You must not blame the dog, Mary, for he does not know it is wrong for him to play with your doll. I hope this will be a lesson to you hereafter, to put your things away when you are through playing.”

This simple story contains two lessons. First, Mary developed a habit of leaving her books and playthings around, so her mother had to pick them up and return them to their proper places. Mary’s books became spoiled, and her toys were broken. For most families, resources such as time and money for children were scarce. Thus, children were taught to take care of their possessions since they might be difficult to replace. The second lesson relates to the treatment of less-fortunate beings — notice how the mother says that the dog does not know that it is wrong to play with Mary’s doll. The mother is telling Mary to set an example and not to blame others for her own carelessness.

In America, the Victorian doll was a pragmatic teaching device. Doll historian, Miriam Formanek-Brunell asserted that beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, American men and women created dolls that were distinct from those made in Europe. The gender-based traditions that emerged in Victorian America produced uniquely American dolls. Women, using individual craftsmanship, produced dolls that expressed soft sensuality, while men created “realistic” mechanical doll products. In 1873, American doll maker, Izannah Walker secured a patent for a press-molded, elastic-knitted, stockinet-fabric that was wonderful for making dolls that were inexpensive. Walker dolls were easy to clean and unlikely to injure children that might fall on them. However, in most Victorian households, where the fathers controlled the purse-strings, to purchase dolls for daughters was not a priority, so mothers often had to improvise. Many middle-class mothers rejected manufactured dolls and encouraged their daughters to made and care for cloth dolls that were thought to teach girls virtue and understanding.

In a story called “The Birth-Day,” written during the 1870s, the absence of a doll is used to teach moral values. In this story a widower named Mr. Willson gives his young daughter Alice a coin for her birthday, but he does not tell her how she should spend the money. Alice tells him that she wants to buy a new doll. He responds, “Is that the best use you can make of it?” Alice replies, “Yes, I am sure a new doll is what I want most.” Instead of taking her directly to the toyshop, he takes her to a very poor neighborhood. In an attic apartment the two find a poor woman sitting near the small window, stitching a shirt. The room is sparsely furnished, and two sick children, who might have been about three or four years old, lay asleep on the floor. The children have not eaten because their mother cannot afford any food — the family has recently been burned out of their home. Alice listens to their story and then discretely leaves her coin behind as they leave the tiny apartment. Mr. Willson seeing his daughter’s generosity, later tells her, “I could not give a present to you and the poor woman too, so I gave it to you to see what you would do with it. I am pleased with your choice, and so I am sure your mother would have been, if she had lived to see your self-denying conduct.”

The absence of the mother figure in this story is significant for the girl to desire a store-bought doll. The moral lesson comes from the girl’s priorities that are demonstrated through her choice to give her gift away. Beyond the moral lesson of charity, this story provides a practical lesson for girls – the poor mother who sews to earn money in the home may earn a small wage, but her efforts demonstrate that she is worthy of charity.

In 1896 Caswell Ellis and G. Stanley Hall published a survey that focused on how children played and interacted psychologically with dolls. It also examined child rituals related to doll play such as naming, feeding, discipline, and how children created imaginary social lives for their dolls. The Ellis & Hall study found that perhaps nothing so fully opens up the child’s soul in the same way that well-developed doll play does. Ellis and Hall said: “Whispered confidences with the doll are often more intimate and sacred than with any human being. The doll is taught those things learned best or in which the child has most interest. The little mother’s real ideas of morality are best seen in her punishments and rewards of her doll. Her favorite foods are those of her doll. The features of funerals, weddings, schools, and parties which are re-enacted with the doll, are those which have most deeply impressed the child. The child’s moods, ideals of life, dress, etc., come to utterance in free and spontaneous doll play.”

The Ellis and Hall study found that the educational value of dolls was enormous, and that doll passion was strongest for children between the seven and ten years of age, reaching its climax between eight and nine. Ellis & Hall commented that a child’s doll: “Educates the heart and will, even more than the intellect, and to learn how to control and apply doll play will be to discover a new instrument in education of the very highest potency.” The study concluded that: “Many children learn to sew, knit, and do millinery work, observe and design costumes, acquire taste in color, and even prepare food for the benefit of the doll. Children who are indifferent to reading for themselves sometimes read to their doll and learn things they would not otherwise do in order to teach it — or are clean, to be like it.”

While parents used dolls as instruments of control so that girls were taught the mundane tasks of domesticity — for girls — dolls became vehicles for flights of fancy. During doll play, girls made and controlled the rules for play, and dolls provided girls with freedom for self-expression. The irony was that with this imagined-freedom and control in doll play, girls also received the practical socialization and instruction that parents wanted them to get. The reality of child culture meant that in the hands of children, dolls became vessels for the children’s imaginations. Applying these educational perspectives today, we can create dolls and toys that are neutral and vessel-like so that children can work through the issues of their daily lives. Doll designers today need to remember the essence of “childness” – children who can happily entertain themselves with an empty box once the novelty of the toy contained within that box has worn off, have the ability to create imaginary worlds that hold very real solutions. These inner worlds are necessary. When our toys create total-entertainment-experiences, we do not need to develop our own imaginations, and thus, we loose our ability to imagine. If you look at creative people, they need a lot of time alone – for whatever reason – this is the time and place where they develop ideas. When children are young, we need to provide them with space for imagining so they can discover practical insights and prepare for the adult world.

Sources used:

Calvert, Karin, Children in the House: The Material Culture of Early Childhood, 1600-1900, (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1992), pp.109-112.

Child, Lydia Maria, Little Girl’s Own Book, (New York: Edward Kearney, 1843), pp. 78-82.

Caswell Ellis and G. Stanley Hall conducted a survey of based upon informal examination of children from many different ages that was circulated as a questionnaire among eight hundred teachers and parents. The survey focused on the types of dolls that children preferred, how they played and interacted psychologically with dolls, and doll/child rituals such as naming, feeding, discipline, sleep, hygiene, sickness and death and the doll’s social life. The results were published in “A Study of Dolls.” Pedagogical Seminary. Vol. 4 (December 1896): 129-175.

Farrar, E.W.R., The Young Lady’s Friend, (Boston: American Stationer’s Co., 1837).

Fromanek-Brunell, Miriam, Made to Play House: Dolls and the Commercialization of American Girlhood, 1830-1930, (Baltimore, MD.:Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), p. 2.

Hewitt, Karen (and Louise Roomet), Educational Toys in America: 1800 to the Present, (Burlington, VT.: The Robert Hull Fleming Museum, University of Vermont, 1979), pp. 8-10.

Knight, Helen C., “School Learning,”The Mother’s Assistant, and Young Lady’s Friend, (Boston: William C. Brown, 1849), 14: 1 (January 1849), pp. 9-12.

Leslie, Madeline. “The Birth-Day,” The Silk Apron and Other Stories. (Boston: Henry A. Young, circa. 1870), pp. 34-43.

McGuffey, William Holmes, “The Torn Doll,” in Second Eclectic Reader, (New York: American Book Company, 1881, 1909), pp. 51-53.