Marketing a Female Ideal in a New America

September 24, 2014

Female industry would temper the steel of American democracy, which was still considered to be a political experiment; time and its prudent usage would be the means for a young America to steer a safe course. Politically connected and Irish-born, Mathew Carey (1760-1839) immigrated to Philadelphia and established a printing and publishing house with seed-money supplied by the Marquise de Lafayette (Leary 1984: 20). Carey was a founding member of the First Day Society, a secular Sunday school established in Philadelphia in 1790 promoting literacy education (Rainier 1996: 79). Carey hoped to cultivate a broad audience of female readers in the new America and published The Lady’s Pocket Library (1792) offering prescriptive advice on life and comportment. Carey published the first American edition of Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Women in 1794 (Green 1985: 24). He published everything from romances to religious tracts, but recognized that the Word was the American bestseller. He earned his fortune and reputation by publishing the first American Catholic Bible and numerous editions of the King James Version of the Bible (Leary 1984: 79).

Carey also published the first bestselling novel in American. American-born Susanna Rowson (1762-1824) wrote Charlotte Temple: A Tale of Truth in the British style of the novel and it was England in 1790. In her introduction, Rowson wrote “I flatter myself, be of service to some who are so unfortunate as to have neither friends to advise, or understanding to direct them, through the variations and unexpected evils that attend a young and unprotected woman her first entrance into life (Rowson 2009: 7).” This cautionary tale described the seduction, and subsequent betrayal, of an unworldly boardinghouse student by a young British army officer. Betrayed first by a trusted teacher, she was lured across the Atlantic to America where her family could offer no guidance. Abandoned, pregnant, and destitute – Charlotte represented every parent’s worst nightmare – and she presented a warning to young women to avoid rakish men. After giving birth to a girl without assistance, Charlotte lost her senses (what Sarah Fielding referred to as “calm mind”), and tragically died alone.

Columbia was in the midst of her awkward youth. In 1812, Carey wrote Rowson, “Charlotte Temple is by far the most popular & in my opinion the most useful novel ever published in this country & probably not inferior to any published in England (Bradsher 1912: 50).” He continued, “… It may afford you great gratification to know that the sales of Charlotte Temple exceed those of any of the most celebrated novels that ever appeared in England. I think the number disposed of must far exceed 50,000 copies; & the sale still continues. There has lately been published an edition at Hartford, of as Fanning owned 5000 copies, as a chapbook – & I have an edition in press of 3000, which I shall sell at 50 or 62 ½ cents (Bradsher 1912: 50).”

Hannah Webster Foster (1759-1840) anonymously wrote the second best-selling American novel called The Coquette, or, The History of Eliza Wharton: A Novel Founded on Fact (1797), based loosely upon the life of poet Elizabeth Whitman (1752-1788) who rebelled against gender limitations in real life. This story presented an opposite extreme from Charlotte Temple by depicting a thirty-seven year old spinster who sought an egalitarian marriage in her youth. The Coquette, first published in Boston by S. Etheridge, described American locations like those in Charlotte Temple that became popular tourist destinations. Eliza rejects many suitors, only to choose the wrong man as a husband. In a tragic story of self-destruction, Eliza is a strong woman of independent means, who demonstrates undesirable characteristics and dies alone and friendless in childbirth. In the story, Eliza’s virtuous friend Lucy Sumner (happily immersed in a good marriage) advises: We are dependent beings; and while the smallest traces of virtuous sensibility remain, we must feel the force of that dependency in a greater or lesser degree. No female, whose mind is uncorrupted, can be indifferent to reputation. It is an inestimable jewel, the loss of which can never be repaired. While retained it affords conscious peace to our minds, and insures the esteem and respect of all around us (Foster & Locke 2009: 132).”

While Austen was beginning to draft her first novels in epistolary form, Columbia subverted her former mother country England with a natural beauty rather than the more flamboyant beauty established in the European courts. Industry was depicted as the feminine ideal in various religious, social, and political messages in order to develop Columbia’s character. While the United States won economic independence, America remained culturally dependent on England until the conclusion of War of 1812. Cosmopolitan Americans continued to read British books, order British products, and emulate English models of metropolitan behavior. Teaching literacy to the working class children spread throughout American communities shortly after it spread through British communities and expanded markets for literature.

Bibliography

Bradsher, Earl L. Mathew Carey, editor, author, and publisher: A Study in American Literary Development. New York: Columbia University Press, 1912.

Foster, Hannah Webster, and Jane E. Locke. The Coquette: the history of Eliza Wharton, a novel founded on fact by a lady of Massachusetts. [Charleston, N.C.]: BiblioBazaar, 2009.

Green, James N. Mathew Carey, Publisher and Patriot. Philadelphia: The Library Company of Philadelphia, 1985.

Leary, Lewis. The book-peddling parson: An account of the life and works of Mason Locke Weems, patriot, pitchman, author, and purveyor of morality to the citizenry of the early United States of America. Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books, 1984.

Reinier, Jacqueline S. From Virtue to Character: American Childhood, 1775-1850. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1996.

Rowson, Susanna. Charlotte Temple: A Tale of Truth. Rockville MD.: Serenity Publishers, 2009.

Austen Counters American Captivity Novels

September 23, 2014

Jane Austen’s work was not in sync with the emerging American nationalism that was a new social construct of imagined communities (not naturally expressed in language, race or religion) as Columbia’s citizenry moved toward a single overarching national identity. The frontier challenged any fictional portrayal of women having niceties based solely upon virtue. Ann Eliza Bleecker (1752-1783) spawned a homegrown American genre in the form of the captivity novel. The posthumous publication of her History of Maria Kettle (1797) set during the French and Indian War containing graphic scenes of violence presented epistolary prose in the British style that was exciting to readers. No English woman would have witnessed the brutal murder of her children by Native Americans, or have been stripped of her “habits, already rent to pieces by brier, and attired… with remnants of old blankets (Bleecker 2010: 19).” Bleecker’s exaggerated style created a hauntingly brutal journey into a conversation on the American frontier. It inculcated moral lessons that assured its captive protagonist, married at the age of fifteen years to a farmer and immersed in innocent righteousness, would be returned to the loving arms of loved ones.

In celebration of the first day autumn, a sample of my mother’s stitching:

“Republican womanhood,” a concept of American womanhood described by historian Linda Kerber, to define the notion that the Republican mother integrated political values into her domestic life. She was dedicated to the nurturing of public-spirited male citizens, and infused her sensibilities of virtue into the young country. This reconciled politics and domesticity and justified the status quo of coverture. For instance, P. -J. Boudier de Villemert in his The Ladies’ Friend: Being a Treatise on the Virtues and Qualifications which are the brightest Ornaments of the Fair Sex, and Render Them most Agreeable to Sensible Part of Mankind (1781), asserted that a woman should place her whole affections on her family, which made the mother the ideal parent to rule the “gentle empire” of the home.

However, a woman’s worth on the frontier (without the established class system found in England) was measured by her service to God and neighbor. American women grappled with newly defined gender roles. As in literary fairy tales, ordinary women were tested in daily life and exhibited quiet heroism when their world was economically destabilized; they often employed an unrecognized female-managed “grey” economy dating back to the Revolution when men were on the warfront. This verse of Judith Sargent Murray (1751-1820) in her collection of essays called The Gleaner (1798) reflects a rarely delineated sensibility of American womanhood cultivated in Columbia’s less-structured class system:

I love to trace the independent mind;

Her beamy path, and radiant way to fine:

I love to mark her where disrob’d she stands,

While with new life each faculty expands:

I love the reasoning which new proofs supplies,

That I shall soar to worlds beyond the skies;

The sage who tells me, spirit ever lives,

New motive to a life of virtue gives.

Blest immortality! – enobling thought!

With reason, truth and honour, richly fraught –

Rise to my view – thy sweet incentives bring,

And round my haunts thy deathless perfumes fling;

Glow in my breast – my purposes create,

And to each proper action stimulate (Murray 1992: 493).

In marriage as in fairy tales, the male reflected the active side of the pairing, while the female reflected its passive more receptive side. Traditional parental influence waned in relation to a daughter’s marriage prospects during the 1790s. American women practiced more freedom in choosing marriage partners as romantic love and premarital sex grew. Single women who did not correspond to the status quo were marginalized. Literature of the day justified this conversation by placing women into a model wives as the purveyors of morality. American women were active out of necessity. Where in Sense and Sensibility, a physician is called when Marianne Dashwood becomes dangerously ill to administer the more psychologically dramatic therapy of bleed letting (suggesting a connection to the upper ranks of society), more conservative remedies would be employed by midwifes in rural America.

Marriage was had become a rite into retirement, and not necessarily the enchanted dream of happily-ever-after. Once a woman wed, under coverture she became a mere cipher. The legal doctrine of coverture declared that a husband and wife became but one person in marriage – that person was the husband whether he lived by virtue or vice. A married woman was considered to be sub potestati viri – under the power of her husband – and therefore she was unable to make contracts or establish credit without her husband’s consent. The husband was liable for his wife’s support, but his legal obligations to his wife extended only to necessities – what she needed to survive. In practice, everything beyond the wife’s mere maintenance was dependent upon her husband’s sense of propriety or generosity.

Bibliography

Bleecker, Ann Eliza. The History of Maria Kittle: in a Letter to Miss Ten Eyck. Glouchester, U.K.: Dodo Press, 2010.

Murray, Judith Sargent. The Gleaner. Schenectady, NY.: Union College Press, 1992.

Cousins Britannia and Columbia and the Evils of Novel Reading

September 22, 2014

British essayist and lexicographer Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) first coined the term “Columbia” to represent the symbolic female personification of the American colony in a 1738 issue of Gentlemen’s Magazine. Johnson defined active as “that which acts, opposed to passive, or that which suffers (Johnson 1785: 1: ACT),” and he defined passive as, “receiving impression from some external agent (Johnson 1785: 2: PAS).”

In traditional fairy tales the male represented the active side of human nature, while the female represented human nature’s passive more receptive side (Meyer 1988: 73). American publishers during the early Republic were especially sensitive to the semantics of active and passive in promoting a strong new America, and American publications promoted feminine virtue as a tool for building nationalism. However, they remained in accord with earlier British essayists Joseph Addison and Richard Steele who warned of the deplorable effects of fashionable education on young women: “From this general folly of parents we owe our present numerous race of coquettes (Lasch 1997: 68 and Tise 1998: 362).” They suggested that raising daughters to be “artful” made them fair game for seducers, when parents should rear daughters to make them morally attractive as marriage partners for upwardly mobile young men.

While Jane Austen was in sync with the contemporary Anglo-American sensibility that young women should not have any exaggerated sense of self-worth, the dependency of her heroines upon reputation was too akin to the sense of dependency experienced by men in colonial America. The memory of economic and cultural dependency on the mother country lingered undermining national confidence. American women craved British literature during the 1790s because it did not mirror tumultuous conditions of contemporary life. American publishers in literary hubs including Philadelphia, Baltimore, Boston, Georgetown, and New Haven, drew upon the British female writers to attract new female readers. However, American publishers were slow to cultivate a sophisticated readership.

In England, as well as in the Colonies, an idle “novel reading” woman was seen not only as a burden to her family but also as a risk for becoming immoral. Reading was not a leisure activity for women in the new America. Within communities where there was very little individual privacy, one frivolous woman in a household could create scandal for the family patriarch resulting in hardship to the entire family since patronage more than inheritance influenced credit. Congregational clergyman Reverend Dr. Enos Hitchcock (1745-1803), in his epistolary novel Memoirs of the Bloomgrove Family, composed a series of letters to Martha Washington explaining how European educational systems were not applicable in the United States: “it is now time to become independent in our maxims, principles of education, dress, and manners, and we are in our laws and government (Hitchcock 1790: 15-7).”

Bibliography

Hitchcock, Enos. Memoirs of the Bloomsgrove Family: In a series of letters to a respectable citizen of Philadelphia. Containing sentiments on a mode of domestic education, suited to the present state of society, government, and manners, in the United States of America, and on the dignity and importance of the female character interspersed with a variety of interesting anecdotes. Boston: Thomas and Andrews, 1790.

Johnson, Samuel. A dictionary of the English language in which the words are deduced from their originals and illustrated in their different significations by examples from the best writers. London: J. F. and C. Rivington, l. Davis, T. Payne and Son, T. Longman, B. Law [and 21 others in London], 1785.

Lasch, Christopher, and Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn. Women and the common life: love, marriage, and feminism. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1997.

Meyer, Rudolf. The Wisdom of Fairy Tales. Edinburgh: Floris, 1988.

Tise, Larry E. The American Counterrevolution: A Retreat from Liberty, 1783-1800. Mechanicsburg, PA.: Stackpole Books, 1988.

Diolog[ue]s and Conversations

September 18, 2014

Emma (1814) was the only work Jane Austen (1775-1817) to be published in the United States during her lifetime. Austen’s romantic fiction remains more popular in the United States than the work of gritty bestselling American female authors of the same era including Susanna Rowson (1762-1824) and Hannah Webster Foster (1758-1840). Austen merged several female literary genres including the fable, the dialogue, and epistolary fiction to create conversations that women could emulate. The semantics of conversation in the context of Austen’s work refers to “behavior; manner of acting in common life (Johnson 1785, 2: CON).” American publishers did not embrace Austen’s work until the 1830s, and the choice of Emma as her introduction to American readers creates a curious subtext of changing women’s roles that came with the emerging American nationalism between 1790 and 1820. Sensibilities of disenchantment run throughout Austen’s plots creating adult exemplum without fairies. The enduring American fascination with Austen’s character, as well as the authoress herself, has lingered with the excitement of a meeting between two cousins long-separated by a family dispute; it reveals an inclination of American readers to read about domestic conflicts in the private sphere abroad rather than public conflicts mirrored in the familial sphere at home in the United States.

Women were generally self-taught and garnered intellectual access to male-dominated fields through the genre of the dialogue or conversation. The dialogue provided a non-threatening literary mechanism so women could read about science without drawing attention. Austen would have been familiar with Sarah Fielding (1710-1768), the younger sister of novelist Henry Fielding, who wrote the first full-length novel for adolescent girls The Governess, or, The Little Female Academy (1749), which was noted for its innovative adaptation of John Locke’s educational theories. The Governess utilized literary devices innovated by Henry Fielding (1707-1754) but it lacked plot complexities found in novels written for adults. Its frame story centered on the daily activities in a boarding school for adolescent girls – it presented a familiar conversation going on between students and their teacher and among each other.

British editions of The Governess could be found in affluent colonial households and the first American edition was published in Philadelphia in 1791. Its lessons would have been familiar to American girls, but culturally and economically a great divide existed. The vast majority of American girls would have little need to attend to a “female academy” unless their families were affluent enough to pay for finishing schools, they would have been modestly educated at home by mothers using primers that might use fables to inculcate very distinct behavior. Fables and fairy tales in Fielding’s story were repeated as mnemonic devises built upon themes of how passion, lying, and cunning adversely affected a girl’s chances for happiness (Fielding 1968: 280). Fielding employed neither “high-sounding Language, nor the supernatural Contrivances” to tell stories, suggesting to readers that great care be taken not to be “carried away, by these high-flown Things, from that Simplicity of Taste and Manners which is my chief Study to inculcate (Fielding 1968: 166).”

Austen’s characters, like Fielding’s, were seldom elegant, but she resolved plotlines with the moral precision characteristic of didactic fairy tales. Austen’s greatness came from embedding themes utilized by Sarah and Henry Fielding in characters that were placed in conversations familiar to readers in the growing middle-class in an industrializing British society. At a time when every girl had little chance for social advancement beyond her choice in marriage partner, Austen mastered a realistic fairy tale where fantasy was spun into reality transposing ordinary into extraordinary. Austen promoted the notion that a girl’s indigenous goodness in any circumstance would bring goodness into her life, and her success in asserting this logic was that she wrote about conversations that were very familiar to her. Austen would later advise her niece Anna Austen Lefroy, an aspiring novelist; against including desultory conversations in her stories, “You will be in danger of giving false representations. Stick to Bath… there you will be quite at home (Austen 2003: 101).”

Bibliography

Austen, Jane. Jane Austen’s letters. Philadelphia: Pavilion Press, 2003.

Fielding, Sarah. The Governess, or, Little Female Academy. London: Oxford University Press, 1968.

Johnson, Samuel. A dictionary of the English language in which the words are deduced from their originals and illustrated in their different significations by examples from the best writers. London: J. F. and C. Rivington, l. Davis, T. Payne and Son, T. Longman, B. Law [and 21 others in London], 1785.

Re-Searching Shunk, conclusion for now…

September 17, 2014

In the art of war, the esprit des corps – the movement of muscles in unison together with chants, song and loud rhythmic yells – creates euphoric energy in battle. The British confident in their ability to defeat the unseasoned American militia selected Baltimore to be the next target. Prior to the battle, Francis Shunk (1788-1848) quoted the opening lines of “Farewell Song to the Banks of Ayr” (1786), Robert Burns’ farewell dirge to his native land, and wrote, “The dark clouds filled with thunder & rain hastened to verspread [sic] the fermentation. The gloom of approaching night adds terror to all surrounding objects… and here I wonder amidst the contention of elements forlorn and silent depressed and unhappy too well does the tumult of my heart accord with the violence that surrounds. After the battle, Shunk happily anticipated the celebration of victory with friends where he would play Green Grow the Rashes, O (1783) – with all his might on the violin. The British did not anticipate that a gutsy Senator named Samuel Smith would change tactics by instituting regular drills featuring marching songs.

Hence, the Battle for Baltimore as chronicled by Francis Scott Key in “The Star Spangled Banner” proved to be a turning point when British forces were repulsed at Fort McHenry, and the city of Baltimore was saved:

Oh, say can you see by the dawn’s early light

What so proudly we hailed at the twilight’s last gleaming?

Whose broad stripes and bright stars thru the perilous fight,

O’er the ramparts we watched were so gallantly streaming?

And the rocket’s red glare, the bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there.

Oh, say does that star-spangled banner yet wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?

On the shore, dimly seen through the mists of the deep,

Where the foe’s haughty host in dread silence reposes,

What is that which the breeze, o’er the towering steep,

As it fitfully blows, half conceals, half discloses?

Now it catches the gleam of the morning’s first beam,

In full glory reflected now shines in the stream:

‘Tis the star-spangled banner! Oh long may it wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave!

And where is that band who so vauntingly swore

That the havoc of war and the battle’s confusion,

A home and a country should leave us no more!

Their blood has washed out their foul footsteps’ pollution.

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave:

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave!

Oh! thus be it ever, when freemen shall stand

Between their loved home and the war’s desolation!

Blest with victory and peace, may the heav’n rescued land

Praise the Power that hath made and preserved us a nation.

Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just,

And this be our motto: “In God is our trust.”

And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave!

A poor farm boy in a multicultural world. Be not deceived, my friends, the carefree days of youth amang the lasses, O, do not a wayfarer still. Mr. Chunk, as he was sometimes called, stayed close to home and hearth, becoming a governor of Pennsylvania who built public institutions of learning and was an early proponent of married women’s property rights.

Next we will explore Jane Austen in a new America…

Re-searching Shunk, continued

September 16, 2014

Issachar Bates (1758-1837) lamented the hypocrisy of elected leaders who in the name of God, raved about freedom yet allowed slavery to continue, and wicked priests who allowed denominational pride to get in the way of fighting for right. Bates walked several thousand miles through the Midwest preaching his concept of the Rights of Consciousness:

RIGHTS of conscience in these days,

Now demand our solemn praise;

Here we see what God has done

By his servant Washington,

Who with wisdom was endow’d

By and angel, through the cloud,

And led forth, in Wisdom’s plan

To secure the rights of man.

Fortuna introduces each nation to her own ethos. The British, outraged by American attacks upon Canadian forces in border towns deemed to be outside civilized laws of warfare issued orders to destroy and lay waste to vulnerable targets. Baltimore, Washington, and Philadelphia looked to be the most promising. The British capture of Washington, D.C. in the autumn of 1814 was the only occasion since the Revolutionary War when a foreign power captured and occupied the young nation’s capital. British forces, though inferior in numbers, in a spectacular ten-day campaign won victory over inexperienced and undisciplined American forces. Federal government leaders who made the most of Washington’s legacy after his death made the decision not to defend the Capital – his namesake. At dawn on August 24, the British marched via the Bladensburg Road towards Washington. American forces proved insufficient as Ross’s forces easily broke trough their positions before the British approached Washington. The British could find no American official to negotiate surrender of the city. Officers dined at the abandoned presidential mansion before ransacking and burning it.

Francis Rawn Shunk (1788-1848), a humble and benevolent fortune hunter saw the United States as a land abounding in inexhaustible resources. He began to study law with Thomas Elder in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania and soon hired Francis to write practical documents before volunteering to serve at the Battle for Baltimore. Shunk scribbled this poem (excerpted from page 50 of his journal):

It sheds upon my soul a melancholy hue

Its short-lived influence shall my bosom fill

And teach the lesson of departing time

When fine delights fill my soul with

Thoughts serene on things above

Where time & chance & misery all shall yield

To heavenly peace & everlasting love.

This must fond inducements like pure zest

Yield up their joy to cruel unrelenting fate

Thus kink endearments mild celestial brand

That in its wove in covers of peace & live by love

So rudely torn fate’s rough iron hand

Is torn asunder by fate’s unrelenting hand.

And kindred spirits doomed – apart to rove.

Shunk borrowed a copy of William Wirt’s The Old Bachelor to read on his off-duty hours. Still green to the ways of the world, he quipped: “The knowledge of men is an important acquisition yet it is not always a source of Satisfaction.” He scribed thoughts on the dichotomy of dependence: “Dependence is that relation which subsists between master and servant, and in which, the wile of the latter is absorbed in the former and is subject to his commands – without resistance – he is a mere machine.” Shunk concluded, “The degrees of this relation are various and extensive; its existence is almost universal, it is not confined to Slaves, properly speaking, that finds its way into all ranks and Conditions of life.”

Shunk felt that worldly knowledge of men causes regret and mortification that outweighs the virtues discovered. He leveraged his self-education to rise in rank. He, a poor schoolteacher, garnered surveying experience. Francis felt that if Americans did not confront the countries that bullied them, their newfound independence would have little meaning. However his view of the conflict evolved as he experienced the hardship of war. He wrote in his journal, “Did kings & conquerors in the hours of serious affliction weigh their glory and their fame against the wretchedness they have produced?”

Re-searching Shunk

September 15, 2014

I am transcribing an old journal from the Battle for Baltimore written by an young Francis R. Shunk. In 2001, a small manuscript containing the writing of Francis Rawn Shunk (1788-1848) was found along with various ephemera in the Marguerite Archer Collection housed in San Francisco State University’s J. Paul Leonard Library. This seventy-page manuscript contains Shunk’s observations from September 5 to November 3, 1814. And my work will likely follow that time frame two hundred years later. Born in the rural village of Trappe, in Montgomery County Pennsylvania, he was the son of a poor farmer and his wife. Shunk struggled to educate himself. His parents, although unable to spare his time contributed to farm work, provided him with a loving home. Shunk’s childhood and youth were mostly devoted to manual farm labor.

Shunk was kind, industrious, and devoted to self-improvement. He recognized the need to cultivate an advantageous patron in order to climb out of grinding poverty. He attended a common school in Trappe. When he was fifteen years old, Shunk was hired as an instructor at that common school. He worked as a teacher during the few months of the year that the school was in session, and the rest of the time he worked as a farm laborer. Books were rare. Francis read each book that his hands reached with deep interest, not lounging on a sofa or around a marble center-table brightly illumined with an astral lamp, but often in a chimney corner, by the light, which a wood-fire or its embers reflected. What he read he pondered until it became part of his mental being.

A Day of Remembrance and Service

September 11, 2014

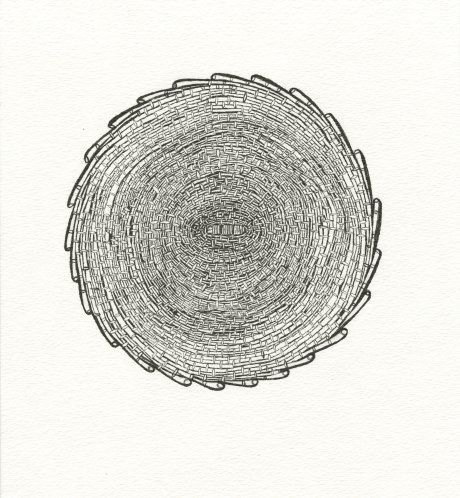

Drawing of a basket bottom by Meredith Eliassen

Happy Birthday CH!

When I return, a journey back two centuries to 1814 with a young soldier who volunteers to defend his country… and his reflections.

California Indian Baskets – A Brief Historical Perspective

September 10, 2014

At the passing of a relative or loved one, aboriginal Californians wailed and mourned – ethnographers referred to this practice as a “cry.” Coast Miwok living in Marin County believed that the spirits of their ancestors traveled beyond Point Reyes, California, over the water west toward the setting sun. The setting sun created a line over the surf thought to lead the way to the home of the dead. Olompali was the site for annual mourning ceremonies that had a traditional burning ground near the village for cremations.

Sir Francis Drake in command of the Golden Hind made the first European contact with Coast Miwok in June 1579. The ship’s chaplain and diarist Francis Fletcher described them as “of a tractable, free and loving nature, without guile or treachery.” On 21 June, the English presented Coast Miwok leaders with shirts and linen cloth. In turn, the tribe presented the visitors with feathers, net caps, quivers for arrows, and animal skins. Fletcher chronicled how they returned to their homes and commenced with horrifying cries of lament, as if they were mourning the dead. Two days later a larger procession came to the invaders with more offerings: the men left gifts of bows; and women and children followed with additional gifts; the women displayed violent physical expressions of mourning to the point of inflicting bodily self injury.

Anthropologists speculated that when the Coast Miwok met the Europeans they assumed, “they were looking upon relatives returned from the dead, and hence performed the usual mourning observances.” American anthropologist Alfred L. Kroeber (1876-1960) speculated that the baskets historically made only by the Coast Miwok, Pomo, Lake Miwok, and Wappo societies, “served as gifts and treasures; and above all they were destroyed in honor of the dead.” Three more days passed, and an even larger group came on 26 June. In this group, each woman carried a round basket filled with offerings including root made into meal, broiled pilchard-like fish, and seed and down of a milkweed-type plant. Women made elaborate baskets for rituals, both diplomatic and sacred; sacred mourning basket were filled with what the diseased would need for the journey to the land of the dead; and the baskets were destroyed to release the spirit of the basket contents and the natural materials used to make the baskets. At the conclusion of the diplomatic ceremonies with Drake, the Coast Miwok acted as if releasing the spiritual energy of the dead ancestors as they, “again departed, giving back to the English everything they had received.”

At the time of first European contact, the indigenous California population was estimated to be from 10,000 to 15,000. Each consecutive wave of invaders brought some form of technology that altered the biotic circumstances of the land. The Coast Miwok took the brunt this as their territory lay north of San Francisco Bay at the entryway to California inland areas rich in natural resources. Radically reliant upon their immediate surroundings, Europeans brought of non-native invasive plants and animals that drastically altered the environment. Over the subsequent generations, logging, sheep and cattle ranching, dairying, cultivation, commercial fishing, and urbanization all took their toll.

The first Spanish penetration into Coast Miwok lands occurred when a 200-ton Spanish ship San Agustin under Portuguese Sebastian Rodriguez Cermeño sailing from Manila traveled up the Petaluma River in July 1595. Cermeño’s scribe chronicled: “the Indian treated the Spaniards to his acorns and the Captain declared that no one should do them any harm or take anything away from them.” The Spanish governed Alta California under a missionary/military system. Mission staff, as well as the limited basket-making materials found adjacent to missions dictated the types of baskets that were constructed, which curtailed the construction of some indigenous basket designs over time. The Spanish authorities banned controlled burns practiced by Native Californian, disrupting the abundant supplies of seed crops, forage for wildlife, and reliable human food supplies. Many of the Coast Miwok at Olompali were baptized at Mission San Jose de Guadalupe between 1816 and 1818 at a time of sweeping small pox epidemics. The best basket making supplies diminished without the controlled burns forcing many Coast Miwok to join the mission system. Neophytes enjoyed less varied diets and living conditions, and the Coast Miwok population was nearly depleted during the years of Franciscan proselytization. German-Russian painter Louis Choris (1795-1828) traveled with the Romanzoff expedition in search of a northwest passage. Choris chronicled the symptoms of extreme trauma among indigenous residents of Mission San Jose in his paintings, at one time noting, “I never saw one laugh… They look though they are interested in nothing.”

Russians arrived along the Sonoma County Coast in 1803 and established Fort Ross (Крепость Россъ), and Bodega Bay located in Coast Miwok territory became as the Russian port of entry to the California fur trade. Admiral Ferdinand Petrovich von Wrangell (1796-1870) served as the Governor of the Russian American Company settlements in North America. Wrangell discerned that the Coast Miwok easily learn diverse arts and crafts, but did not distinguish between the Bodega Miwok and the Pomo when he brought indigenous-made artifacts back to Russia and Europe. The Russians imported a social hierarchy of Russians (at the top), Creoles, Aleuts, and Native Americans (at the bottom), but they did nothing to coercively alter Coast Miwok / Pomo culture, so they offered indigenous Californians an alternative to Spanish domination.

The Coast Miwok and other tribes adjacent to the San Francisco Bay were on the front lines of cultural battles with Anglo-American invaders in California. Coast Miwok lands increasingly became home to Mexicans, Californios (of mixed racial heritage including European, indigenous Mexican, African, and indigenous Californian), Anglo-Canadians, Russians, Creoles, Aleuts, and Kanakas (indigenous Hawaiians). The Hudson’s Bay Company hoped to gain a foothold in California’s lucrative hide and tallow trade during between 1841 and 1844. Their tactic was to make aboriginals dependent: “for having abandoned the use of all their former arms, hunting and fishing implements, and clothes, they can no longer subsist without the guns, ammunition, fish-hooks, blankets and other similar articles, which they receive only from the British traders.”

In early 1848, during the early months of the California gold rush before traders could obtain tin pans for gold mining from the East Coast, Native Californians produced shallow baskets for “gold panning” that were sold to miners. This ignited consumer demand for California Indian baskets using new materials and shapes to accommodate jars, whiskey bottles, and goblets. During the Victorian era, miniature baskets came into vogue.

Americans observed Coast Miwok prudently gathering seeds and digging bulbs and tubers, they derisively labeled them “digger” Indians. With the Civil War, the United States Congress passed legislation, terminating titles to almost all of Indian land in California, stripping most California tribes of lands. Basket makers continued to cultivate and harvest basket-making materials from public lands. Stripped of homelands, anecdotes derisively described how now transient Coast Miwok were “self-exiled, poured over driftwood for salvage,” and how Coast Miwok women were seen, “trudging along with the children and bearing huge baskets on their backs strapped to the forehead… crammed full with dirty blankets, camp utensils, dried fish, pinole and papooses.”

When the 49’ers first searched for gold, they traded manufactured goods for shallow baskets for panning with the California Indians that were used to “pan” for gold, once they got mass produced pans the baskets were abandoned.

California Indian baskets changed with the times to suit the need at hand, but they never passed into extinction, they were scattered to the winds like acorns carried to distant lands by birds. As early as 1898, Bodega Miwok Tom Smith spoke of the necessity for tribal elders to interpret this minority counterculture to the dominant American society and more importantly for tribal posterity: A man with no family has no history and no eyes to see the future. He goes about blind. Our family, our relations, are not only those around us, they are also those who have gone before us. They are our history. They gave us our ways, and we are to be the teachers of our traditions. If we lose our ways, our history, we will be lost and there will be not one to tell us where to go. That’s why those Indian things and doings are so important; they are our eyes and our children’s eyes.

Bibliography:

Federated Coast Miwok (FCM). We Are Still Here: A Coast Miwok Exhibit. Bolinas: Bolinas Museum, 1993.

Greenhow, Robert. The History of Oregon and California and other Territories of the North-West Coast of North America. New York: Appleton, 1845.

Heizer, Robert F. Elizabethan California. Romana, CA.: Bellena Press, 1974.

Kroeber, Alfred L. Handbook of the Indians of California. Berkeley: California Book Company, 1925.

Thalman, Sylvia Barker. The Coast Miwok Indians of the Point Reyes Area. Point Reyes: Point Reyes National Seashore Association, 2001.

Wagner, Henry R. Spanish Voyages to the Northwest Coast of America in the Sixteenth Century. San Francisco: California Historical Society, 1929.