Now, an aside on doll imagery for consideration

December 4, 2014

In 1896 Caswell Ellis (1871-1948) and G. Stanley Hall (1844-1924) published a survey that focused on how children play and interact psychologically with dolls. It also examined child rituals related to doll play such as naming, feeding, discipline, and how children created imaginary social lives for their dolls, which would be illuminated in illustrations by Sarah S. Stilwell. The Ellis & Hall study found that perhaps nothing so fully opens up the child’s soul in the same way that well-developed doll play does. Ellis and Hall reported: Whispered confidences with the doll are often more intimate and sacred than with any human being. The doll is taught those things learned best or in which the child has most interest. The little mother’s real ideas of morality are best seen in her punishments and rewards of her doll. Her favorite foods are those of her doll. The features of funerals, weddings, schools, and parties which are re-enacted with the doll, are those which have most deeply impressed the child. The child’s moods, ideals of life, dress, etc., come to utterance in free and spontaneous doll play.

The Ellis and Hall study found that the educational value of dolls was enormous, and that doll passion was strongest for children between the seven and ten years of age, reaching its climax between eight and nine. Ellis & Hall commented that a child’s doll: Educates the heart and will, even more than the intellect, and to learn how to control and apply doll play will be to discover a new instrument in education of the very highest potency. The study concluded that: Many children learn to sew, knit, and do millinery work, observe and design costumes, acquire taste in color, and even prepare food for the benefit of the doll. Children who are indifferent to reading for themselves sometimes read to their doll and learn things they would not otherwise do in order to teach it — or are clean, to be like it.

Let me briefly visit the seemingly conflicting issue of control related to doll play: while Victorian parents used dolls as instruments of control so that girls were taught the mundane tasks of domesticity — for girls — dolls became vehicles for flights of fancy. During doll play, girls made and controlled the rules for play, and dolls provided girls with freedom for self-expression. The irony was that with this imagined-freedom and control in doll play, girls also received the practical socialization and instruction that parents wanted them to get.

Dolls became neutral vessels for the children’s imaginations where they can work through the issues of their daily lives. The essence of “childness” is universal and timeless – children who can happily entertain themselves with an empty box once the novelty of the toy contained within that box has worn off; having the ability to create imaginary worlds that hold very real solutions; and these inner worlds are necessary. When our toys create total-entertainment-experiences, we do not need to develop our own imaginations, and thus, we loose our ability to imagine. If you look at creative people today, they need a lot of time alone – for whatever reason – this is the time and place where they develop ideas. When children are young, we need to provide them with space for imagining so they can discover practical insights and prepare for the adult world.

Source: Caswell Ellis and G. Stanley Hall, “A Study of Dolls,” Pedagogical Seminary 4 (December 1896): 129-175.

Designing the Girlish Ideal

December 3, 2014

Sarah S. Stilwell Weber (1878-1939) expanded commercial illustration with her unique decorative style and a flair for the exotic. Saturday Evening Post editor George Horace Lorimer (1867-1937) spotted her talent and offered a contract to contribute covers scheduled on a regular basis – however, she declined unsure of maintaining strict deadlines while retaining her artistic integrity with family obligations. Still, Stilwell-Weber managed to create about sixty Post covers between 1904 and 1921. Even when women had no vote, as a graphic artist, Stilwell-Weber earned an equivalent salary to a Supreme Court justice in 1910. As a mother, she brought realism to the subject of childhood when other female artists marketed nostalgia.

A search of census records revealed that Sarah was the youngest daughter of a harness maker named William Stilwell and his wife Isabella who lived in Concordville, Pennsylvania. She attended the Drexel Institute from 1895 to 1900, earning a certificate in Drawing, Painting and Sculpture. An art director from Colliers Weekly initiated her career as a commercial illustrator when he selected a drawing for publication in 1898.

Sarah was among the first female students to make use of studios at Chadd’s Ford along the Brandywine River operated by Howard Pyle (1853-1911). In an interview for Harper’s Weekly, Pyle explained that he wanted students, “to draw a human figure that appeared to stand upon its feet, to move easily and fluently with articulate joints, to breath and live.” She participated in Howard Pyle’s Brandywine classes in the summer of 1899 and February 1900 on scholarships. When Pyle established his school in Wilmington, Delaware, she joined him to continue her studies.

Pyle, who also came from a family with a leather-related business, had the ability to recognize and cultivate budding talent that made him a master teacher. Pyle was concerned about the total visual layout of pages; he taught students the importance of good pictorial composition. Pyle encouraged students to draw the human face and figure from memory rather than to rely continually on models” – Sarah’s career blossomed under his tutelage.

The Hunt, Satisfied… Re-searching Sarah S. Stilwell

December 2, 2014

For researchers and book collectors, the hunt offers thrills that uncover treasures from the past. My first in-depth research project was about a then long-forgotten female illustrator named Sarah S. Stilwell Weber (1878-1939) who came to me through a call for papers for a volume of the Dictionary of Literary Biography on American illustrators. In the end, right before the book went to press, the editors dropped this fantastic artist from the project because she was thought to have had too little output over her career. However, for me, it was too late, I was hooked, but on some level I felt I had failed her by not providing a comprehensive enough profile to convince the editors of her place in American book illustration annals.

In the age of research before Google searches and BookFinder.com, along with the vast amount of digitization had commenced, I was reliant upon the Readers’ Guide to Periodic Literature for doing initial research. This revealed a vague reference to a book by Richard le Gallienne (1866-1947) but cited no title. When I searched OCLC I found a promising title, Mr. Sun and Mrs. Moon (1902), but had no mention of Sarah S. Stilwell. The Gleason Library at University of San Francisco had a copy in its special collections, and on a hunch, I called the librarian and made an appointment and made my way to Lone Mountain.

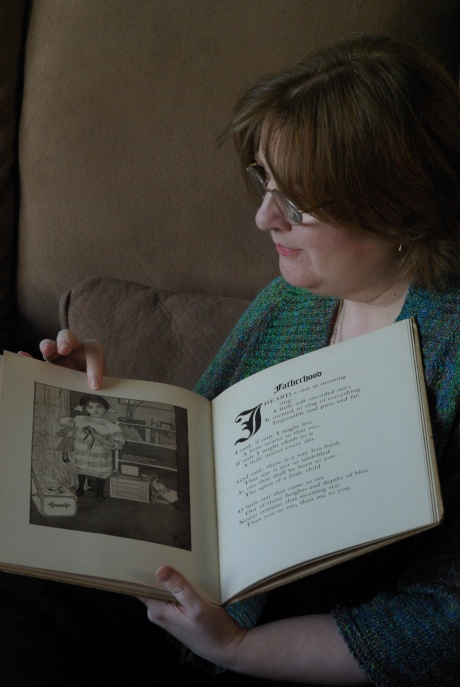

MME with her find. Photographed by R.I. Otterbach, 2014.

When the special collections librarian brought the slim volume out, he looked almost apologetic. I remember being left alone with Mr. Sun and Mrs. Moon and opening it to the title page and sure enough, no illustrator was named. The dedication featured a circular photograph of a lovely young Eva Le Gallienne (1899-1991) before her mother Julie Norregard took her to live in Paris:

“To Eva,

Eva, we were so glad you came,

For life is such a lonely game

With only one to play it, dear –

As Hesper for six long years;

But now the games you have, you two!

We are so glad you came – are you?”

The poems, written with much tenderness, reveal a family in stress. Eva was the daughter of a second marriage that was short-lived, while her older sister Hesper is the daughter of Le Gallienne’s first wife who died in 1894. Even with so much love, there is also a strange ambivalence in the verses. The imagery, however, was light, celestial. As I looked at the strange singular style, I was struck by their dreamy gentle styling. The illustrator’s only apparent signifier was two slippers (that on closer inspection were two small “S”s side-by-side), and in one there were a few scrawled “S”s in the carpet. A chill went down my spine – the illustrations were HERS – just small marks hidden in texture – transparent within a very private book of published verses as if the illustrator were an outsider looking into Mr. Sun and Mrs. Moon’s unsettled lives on the verge of collapse.

I breathed: oh my God! That which had been hidden to me, came into view. I would have that response many times again in my research afterward, but never with the same sense of discovering treasure.

“We are so glad you came – are you?”

For a sampling of Sarah Stilwell Weber’s work, check Illustration Art Solutions online:

http://www.illustration-art-solutions.com/sarah-stilwell.html