Too much politics already… where is little star?

October 11, 2016

“Twinkle, twinkle, little star, How I wonder what you are! Up above the world so high, Like a diamond in the sky. When the blazing sun is gone, When he nothing shines upon, Then you show your little light, Twinkle, twinkle, all the night. Then the traveler in the dark Thanks you for your tiny sparks. He could not see which way to go, If you did not twinkle so. In the dark blue sky you keep, And often through my curtains peep, For you never shut your eye ‘Till the sun is in the sky. As your bright and tiny spark Lights the traveler in the dark, Though I know not what you are, Twinkle, twinkle, little star.” Poem by Jane Taylor (1783-1824), design by Meredith Eliassen, 2015.

Sarah Fielding & the Literary Fairy Tale

August 31, 2016

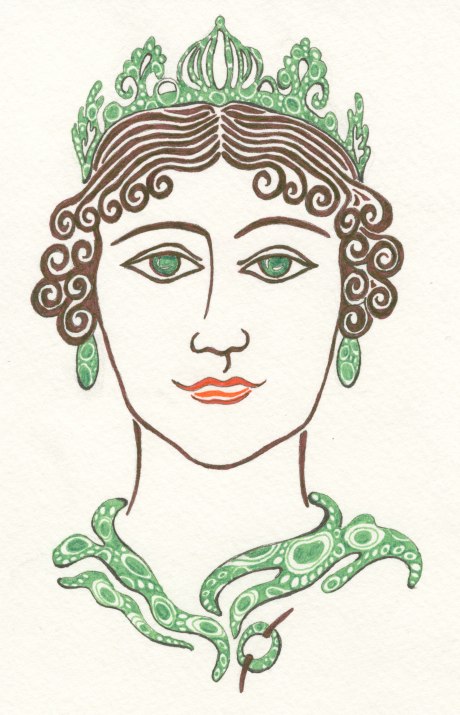

Design of “Princess Hebe” by Meredith Eliassen, 2016

Englishwoman Sarah Fielding (1710-68), the younger sister of author Henry Fielding, created an innovative work that included whimsical stories of fairies, giants, and animals that taught lessons about controlling vanity, envy and pride. Her novel, The Governess, or, The Little Female Academy (1749), taught didactic lessons to girls from eight to twelve years of age. The Governess has been called the first novel for children, but it was actually the first novel written for adolescent girls. Fielding’s logic appeared in genres familiar to females — the fable and fairy tale. The Governess became a textbook; its clean logic was perfect for teaching fundamental critical thinking to girls, its innovative feminine rhetoric remains seminal to understanding early fairy tales published in the United States between 1790 and 1820.

In her Dedication, Fielding referred to John Locke’s pedagogical theories when she asserted an inclination toward moral excellence might be gained with the suppression of passion. John Locke (1632-1704), one of the most influential Enlightenment thinkers, suggested children could be educated to conform with a shift from the physical coercion to more modern psychological maneuvering. Fielding adapted the traditional practice of a tutor (or governor) teaching sons into a suitable literary text designed to teach daughters: “The design of the following Sheets is to endeavour to cultivate and early Inclination to Benevolence, and a Love of Virtue, in the Minds of young Women by trying to shew them, that their True Interest is concerned in cherishing and improving those amiable Dispositions into Habits; and in keeping down all rough and boisterous Passions; and that from this alone they can propose to themselves to arrive at true Happiness, in any of the Stations of Life allotted to the Female Character.”

The Governess was the first novel to depict realistic juvenile characters in recognizable settings. Its frame story centers on daily activities in a boarding school for adolescent girls. The action of the novel begins when Mrs. Teachum’s students resort to violence over apples. The initial conflict creates the justification for imbedding tales that lead to character development. The governess, Mrs. Teachum, employs persuasion rather than force to instruct. Mrs. Teachum encourages the girls to read stories to each other, and then instructs her assistant to point out morals in the stories: “The misses all agreed, that certainly it was of no Use to read, without understanding what they read.” Fielding concluded, “This I have endeavoured to inculcate, by those Methods of Fable and Moral, which have been recommended by the wisest Writers, as the most effectual means of conveying useful Instruction.”

British essayist Joseph Addison asserted that fables flourished during periods “when Learning [was] at its greatest Height.” Readings provoke pupils to confess incidents that build upon themes of how passion, lying, cunning, and envy adversely affect chances for happiness. Fielding led a movement to utilize oral traditions including fables to teach girls good moral conduct. “The Story of Caelia and Chloe,” an exemplary tale, warned of the danger of using deceit and exerting will. Twin sisters, twenty-two years old, meet an intelligent lieutenant colonel named Sempronius. He cannot determine which sister to marry, so he goes to Chloe and explains to her that he loves Caelia and wants to marry her. Chloe dissuades Sempronius by lying about Caelia’s character. Chloe tells him that her sister is prone to horrible fits of rage, and that she would make him a poor wife. Confused by this poor report of Caelia’s character, Sempronius next goes to Caelia with the same message, telling her that he loves her sister and wants to marry her. Caelia, who has a sweet and loving temperament, is disappointed by this confession, because indeed, she loves Sempronius deeply. However, unable to speak badly of her sister, Caelia blesses the union. Sempronius leaves when he notices the difference in behavior between the two sisters. He returns to explain to Caelia how Chloe badmouthed her, but Caelia refuses believe him. Chloe becomes ill when she realizes that Sempronious has caught her in a lie. As Chloe’s lies weigh on her conscience, her “dis-ease” grows. Sempronius leaves with his regiment, and Caelia remains by her sister’s side to nursing her. Chloe grows worse under the weight of her guilt, until she confesses her transgression. Caelia blesses Chloe’s engagement to Sempronius, and peace is restored when the truth because both are equally provided for in the story’s resolution.

The Governess equates happiness with conformity and group cohesion. Mrs. Teachum instructs her assistant to choose fairy tales that illustrate how patience can present opportunities to prevail in adversity: “But neither this high-sounding Language, nor the supernatural Contrivances in this Story do I so thoroughly approve, as to recommend them much to your Reading; except, as I said before, great Care is taken to prevent your being carried away, by these high-flown Things, from that Simplicity of Taste and Manners which is my chief Study to inculcate.”

COMING IN SEPTEMBER… a discussion of media ecology in relation to childhood… stay tuned.

Angelou on the Semantics of Education

August 30, 2016

“Education is man’s most amazing tool… amazing toy, or effective tool, or it can be… man’s most effective weapon. Education” Maya Angelou “Blacks, Blues, Black!,” 1968. Design by Meredith Eliassen

“Blacks, Blues, Black!” (Episode 6: Education)

Conversely, Native Americans in California used baskets as if they are extensions of the human body; infants were immersed in water-holding baskets as they get immersed in culture. Basket makers are engineers who create amplified baskets from spiritualized raw natural materials; as children learned gendered tasks related to basket and net making, they learned cultural values. Here we perceive the concept of ecology as the study of environment and how its structure and content impact human beings. When the United States government attempted to eradicate the tribes in southern Oregon, they destroyed functional Native American baskets as a war tactic. In southern Oregon, during the Rogue River Indian War (1855-1856), vigilantes and army troops attacked Tututni villages employing a military tactic to undermine tribal stability by destroying all baskets and their contents that were use in every aspect of life, because without baskets, the tribes were unable to survive (See note).

In medieval European England, Biblical translator and reformer John Wycliffe (1338-1384) came to regard the scriptures as the only reliable guide to the Truth that came from God. Wycliffe maintained that all Christians should rely on the Bible rather than on the teachings of popes and clerics. He said that there was no scriptural justification for the papacy. In keeping with Wycliffe’s belief that scripture was the only authoritative reliable guide to living a good life, he became involved in efforts to translate the Bible into English as a means of empowering the common folk. Wycliffe asserted that not having English-language Bibles meant that it was not accessible to laypeople, therefore the common people were being deprived of God’s Word because it was written in the language of a foreign people.

Note: Stephen Dow Beckham, Requiem for a People: The Rogue Indians and the Frontiersmen (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971), 27.

The Web of Childhood: Media Ecology and Dolls

February 1, 2016

Dolls are complex and paradoxical toys where subtle issues of parent-child control can come into play. Parents and children had different motives for employing dolls – parents wanted girls to play with dolls for instruction and socialization, and children played with dolls because they were fun. Dolls were used to teach American girls lessons in domesticity, specifically needle-crafts such as sewing and knitting, that were necessary to maintain home economy. In an ephemeral way, dolls before the advent of electronic devices could become an extension of the child’s very being.

“We wove a web in childhood, a web of sunny air.” Quote by Charlotte Brontë (1816-1855), drawing by Meredith Eliassen, 2016.

Prior to the Victorian era, historians agree that doll play for boys and girls was a means for creating inner-landscapes where “problems of being” could be resolved with play. During the early-nineteenth century, German educator, Frederick Froebel (1782-1852) revolutionized early education, when he showed that young children were capable of rapid skill acquisition when they were allowed to use materials that employed their tendency towards active play as they developed their minds. Although Froebel focused on specific games and activities using balls and shapes, he felt that all toys should be suited to the particular intellectual demands of children at specific ages. Thus, the sophistication of the toy or doll was designed to match that of the child. Froebel said: “Play, then, is the highest expression of human development in childhood, for it alone is the free expression of the child’s soul. It is the purest and most spiritual product of the child, and at the same time it is a type and copy of human life at all stages and in all relations.”

With the influence of Queen Victoria (1819-1901), a dichotomy emerged where dolls became the exclusive domain of girls. Queen Victoria was significant in expanding the educational functions of dolls in the nursery. Even before her reign, Princess Victoria collected wood dolls — and with guidance from her governess — she sewed clothing for her dolls until she was about fourteen years old. The Princess’s portrait dolls represented people in the court and famous personalities of her time. These dolls served an additional function beyond being toys; they documented social history in the Royal Household. This use of dolls in socializing girls quickly spread from England to America and remained popular.

Karin Calvert asserted in her book, Children in the House (1992), that parents wanted their children to conform to very distinct and rigid social roles existing for men and women. Boys should “take” their pleasure with active play while girls “busied” themselves by imitating women’s domestic duties. In studying the educational functions of the doll, one must begin by examining gender roles that required girls to need such careful training to be good wives and mothers. Economic and social changes related to the Industrial Age dramatically impacted family life. Not only did fathers leave the immediate household in order to find work, but families also moved to urban areas where there was less child-care support from extended families. For this very reason, women’s literature during the mid-nineteenth century filled a void for women by providing child-rearing advice. Mothers were expected to guide and discipline children on a daily basis, using a combination of love, reason, approbation, and rewards. The Victorian concept of the ideal mother — a woman always available and always loving — was prescribed in women’s literature. She was strict but loving, ever affectionate with her brood, and always successful in commanding absolute obedience from her children. Popular culture exalted the role of mothers, and mothers served as the emotional center of domestic life.

While sewing and textile production was traditionally important to domestic economy along with dairying, food preparation, housekeeping and child care, its importance seemed to increase during the Victorian era. Women sometimes utilized these skills as an occupation to supplement family incomes, but they were seldom able to earn enough to live independent lives. In 1837, Eliza Farrar (1791-1870) commented in the Young Lady’s Friend: “A woman who does not know how to sew is as deficient in her education as a man who cannot write.”

In 1843, Lydia Maria Child (1802-1880), in her classic work, the Little Girl’s Own Book, gave basic instructions for plain sewing, mending, knitting, along with patterns for competing simple projects. She said: “There is no accomplishment of any kind more desirable for a woman, than neatness and skill in the use of a needle. To some, it is an employment not only useful, but absolutely necessary; and it furnishes a tasteful amusement to all. The first and most important branch, is plain sewing. Every little girl, before she is twelve years old should know how to cut and make a shirt with perfect accuracy and neatness. Child also commented that: “At infant schools in England, children of three and four years old make miniature shirts, about big enough for a large doll.”

A girl’s education in sewing occurred at home — she was instructed by her mother, older females in the household, or older friends. However, as a young girl, her education could be self-directed if she had a doll to care for. Children’s magazines such as St. Nicholas, included articles for children with instructions for sewing or knitting, along with doll stories that contained basic instructions for creating doll clothes. Some articles included patterns, but many children had to copy illustrations from books and magazines in order create their own patterns. In the process, they learned all aspects of dressmaking and basic tailoring. “Child included a selection in her book called, “Dolls”: “The dressing of dolls is a useful as well as a pleasant employment for little girls. If they are careful about small gowns, caps, and spencers, it will tend to make them ingenious about their own dresses, when they are older. I once knew a little girl who had twelve dolls; some of them were given to her; but the greater part she herself made from rags, and her older sister painted their lips and eyes. She took it into her head that she would dress the dolls in the costumes of different nations. No one assisted, but by looking in a book called Manners and Customs, she dressed them all with great taste and propriety… I assure you they were an extremely pretty sight. The best thing of all was the sewing was done with the most perfect neatness. When little girls are alone, dolls may serve for company. They can be scolded and advised, and kissed, and taught to read, and sung to sleep — and anything else the fancy of the owner may devise.

In 1848, Mrs. Helen C. Knight actually opposed sending girls to school. She commented in the Mother’s Assistant: The sphere of the female is at home; and an ignorance of her duties there, brings discredit and unhappiness to herself, and discomfort and sorrow to her family. When is the best season for learning these duties? It must be in youth; they must form a portion of every day’s striving and learning; they must be nourished in our daily habits. It is the child which must be taught to take care of its chamber and its drawers, to bear and forbear with its little brother, to come in with its young energies to the help of mother, and to feel the importance of sewing in the manufacture of its own garments.

American textbooks from the Victorian period document gender roles of the time in their texts and illustrations. More than learning to read, children were being educated to take their place in society. McGuffey Eclectic Readers were the most widely distributed school-books in America from 1836 until 1910. Although the McGuffey Eclectic Readers were criticized for being didactic and moralistic, this series is considered by many to be an important force in shaping the consciousness of Middle America. While early editions contain few references to dolls, revisions of the Eclectic Readers contained passages where dolls teach moral lessons about sharing and caring for possessions.

McGuffey’s Second Eclectic Reader contains a lesson called, “The Torn Doll,” where young Mary Armstrong learns the importance of taking proper care of her doll. One day while Mary is playing in the yard, she abandons her favorite doll on the porch where the family dog, named Dash can find it. Dash grabs the doll and roughly plays with it, and tears it. The next morning when Mary finds her broken doll, she harshly scolds the dog. Her mother comes to the dog’s defense and says, “You must not blame the dog, Mary, for he does not know it is wrong for him to play with your doll. I hope this will be a lesson to you hereafter, to put your things away when you are through playing.”

This simple story contains two lessons. First, Mary developed a habit of leaving her books and playthings around, so her mother had to pick them up and return them to their proper places. Mary’s books became spoiled, and her toys were broken. For most families, resources such as time and money for children were scarce. Thus, children were taught to take care of their possessions since they might be difficult to replace. The second lesson relates to the treatment of less-fortunate beings — notice how the mother says that the dog does not know that it is wrong to play with Mary’s doll. The mother is telling Mary to set an example and not to blame others for her own carelessness.

In America, the Victorian doll was a pragmatic teaching device. Doll historian, Miriam Formanek-Brunell asserted that beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, American men and women created dolls that were distinct from those made in Europe. The gender-based traditions that emerged in Victorian America produced uniquely American dolls. Women, using individual craftsmanship, produced dolls that expressed soft sensuality, while men created “realistic” mechanical doll products. In 1873, American doll maker, Izannah Walker secured a patent for a press-molded, elastic-knitted, stockinet-fabric that was wonderful for making dolls that were inexpensive. Walker dolls were easy to clean and unlikely to injure children that might fall on them. However, in most Victorian households, where the fathers controlled the purse-strings, to purchase dolls for daughters was not a priority, so mothers often had to improvise. Many middle-class mothers rejected manufactured dolls and encouraged their daughters to made and care for cloth dolls that were thought to teach girls virtue and understanding.

In a story called “The Birth-Day,” written during the 1870s, the absence of a doll is used to teach moral values. In this story a widower named Mr. Willson gives his young daughter Alice a coin for her birthday, but he does not tell her how she should spend the money. Alice tells him that she wants to buy a new doll. He responds, “Is that the best use you can make of it?” Alice replies, “Yes, I am sure a new doll is what I want most.” Instead of taking her directly to the toyshop, he takes her to a very poor neighborhood. In an attic apartment the two find a poor woman sitting near the small window, stitching a shirt. The room is sparsely furnished, and two sick children, who might have been about three or four years old, lay asleep on the floor. The children have not eaten because their mother cannot afford any food — the family has recently been burned out of their home. Alice listens to their story and then discretely leaves her coin behind as they leave the tiny apartment. Mr. Willson seeing his daughter’s generosity, later tells her, “I could not give a present to you and the poor woman too, so I gave it to you to see what you would do with it. I am pleased with your choice, and so I am sure your mother would have been, if she had lived to see your self-denying conduct.”

The absence of the mother figure in this story is significant for the girl to desire a store-bought doll. The moral lesson comes from the girl’s priorities that are demonstrated through her choice to give her gift away. Beyond the moral lesson of charity, this story provides a practical lesson for girls – the poor mother who sews to earn money in the home may earn a small wage, but her efforts demonstrate that she is worthy of charity.

In 1896 Caswell Ellis and G. Stanley Hall published a survey that focused on how children played and interacted psychologically with dolls. It also examined child rituals related to doll play such as naming, feeding, discipline, and how children created imaginary social lives for their dolls. The Ellis & Hall study found that perhaps nothing so fully opens up the child’s soul in the same way that well-developed doll play does. Ellis and Hall said: “Whispered confidences with the doll are often more intimate and sacred than with any human being. The doll is taught those things learned best or in which the child has most interest. The little mother’s real ideas of morality are best seen in her punishments and rewards of her doll. Her favorite foods are those of her doll. The features of funerals, weddings, schools, and parties which are re-enacted with the doll, are those which have most deeply impressed the child. The child’s moods, ideals of life, dress, etc., come to utterance in free and spontaneous doll play.”

The Ellis and Hall study found that the educational value of dolls was enormous, and that doll passion was strongest for children between the seven and ten years of age, reaching its climax between eight and nine. Ellis & Hall commented that a child’s doll: “Educates the heart and will, even more than the intellect, and to learn how to control and apply doll play will be to discover a new instrument in education of the very highest potency.” The study concluded that: “Many children learn to sew, knit, and do millinery work, observe and design costumes, acquire taste in color, and even prepare food for the benefit of the doll. Children who are indifferent to reading for themselves sometimes read to their doll and learn things they would not otherwise do in order to teach it — or are clean, to be like it.”

While parents used dolls as instruments of control so that girls were taught the mundane tasks of domesticity — for girls — dolls became vehicles for flights of fancy. During doll play, girls made and controlled the rules for play, and dolls provided girls with freedom for self-expression. The irony was that with this imagined-freedom and control in doll play, girls also received the practical socialization and instruction that parents wanted them to get. The reality of child culture meant that in the hands of children, dolls became vessels for the children’s imaginations. Applying these educational perspectives today, we can create dolls and toys that are neutral and vessel-like so that children can work through the issues of their daily lives. Doll designers today need to remember the essence of “childness” – children who can happily entertain themselves with an empty box once the novelty of the toy contained within that box has worn off, have the ability to create imaginary worlds that hold very real solutions. These inner worlds are necessary. When our toys create total-entertainment-experiences, we do not need to develop our own imaginations, and thus, we loose our ability to imagine. If you look at creative people, they need a lot of time alone – for whatever reason – this is the time and place where they develop ideas. When children are young, we need to provide them with space for imagining so they can discover practical insights and prepare for the adult world.

Sources used:

Calvert, Karin, Children in the House: The Material Culture of Early Childhood, 1600-1900, (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1992), pp.109-112.

Child, Lydia Maria, Little Girl’s Own Book, (New York: Edward Kearney, 1843), pp. 78-82.

Caswell Ellis and G. Stanley Hall conducted a survey of based upon informal examination of children from many different ages that was circulated as a questionnaire among eight hundred teachers and parents. The survey focused on the types of dolls that children preferred, how they played and interacted psychologically with dolls, and doll/child rituals such as naming, feeding, discipline, sleep, hygiene, sickness and death and the doll’s social life. The results were published in “A Study of Dolls.” Pedagogical Seminary. Vol. 4 (December 1896): 129-175.

Farrar, E.W.R., The Young Lady’s Friend, (Boston: American Stationer’s Co., 1837).

Fromanek-Brunell, Miriam, Made to Play House: Dolls and the Commercialization of American Girlhood, 1830-1930, (Baltimore, MD.:Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), p. 2.

Hewitt, Karen (and Louise Roomet), Educational Toys in America: 1800 to the Present, (Burlington, VT.: The Robert Hull Fleming Museum, University of Vermont, 1979), pp. 8-10.

Knight, Helen C., “School Learning,”The Mother’s Assistant, and Young Lady’s Friend, (Boston: William C. Brown, 1849), 14: 1 (January 1849), pp. 9-12.

Leslie, Madeline. “The Birth-Day,” The Silk Apron and Other Stories. (Boston: Henry A. Young, circa. 1870), pp. 34-43.

McGuffey, William Holmes, “The Torn Doll,” in Second Eclectic Reader, (New York: American Book Company, 1881, 1909), pp. 51-53.

Volland Publishing and Women artists

December 18, 2014

German-born Paul Frederick Volland established his successful greeting card company in Chicago, Illinois in 1908. However, he hit the jackpot with a series of children’s books about a loveable rag doll named Raggedy Ann. Volland offered opportunities for many women to enter the publishing industry as writers and illustrators. The following are two lesser-known women who also found success with Volland Publishing. M. T. Penny Ross was an active illustrator between 1900 and 1920. The vibrant colors and whimsy of Ross’ illustrations published by the P.F. Volland Company, which included flower children, “Mother Earth’s” children, and our bird children, captivated young children and taught them about nature with easy to remember rhymes.

Pre-1910 – Animal Children

1910 – The Flower Children, P. F. Volland

1912 – Bird Children, P. F. Volland

1914 – Mother Earth’s children, P. F. Volland

1914 – Year with the fairies, P. F. Volland

1915 – Loraine and the Little People of Spring, Rand McNally

1916 – I Wonder Why?

1985 – Get down and come in, Author

Elizabeth Gordon (1865-1922) lived in Chicago Illinois. Began writing as a contributer of special articles from the West for the Portland Transcript, the Bangor Courier, and others, She was the editor of the Children’s Tribune in Minneapolis, 1901-04 and the editor for “Babylan” department of Junior Instructor Magazine 1920-21, and assistant literature cricit for Cumulative Index. She was a member of the League American Pen Women, Storytellers League (Los Angeles and Chicago), Women’s Press Club, Illinois Women’s Press Association, and Midland Authors.

1879 – Among the flowers: a poem

1881 – The world’s future, or the Union leader

1905 – (The) influence of Lucretius

Pre-1910 – Animal Children

1910 – The Flower Children, P. F. Volland

1911 – Some Smile: a Little Book, W.A. Wilde

1912 – Bird Children, P. F. Volland

1912 – Just you, P. F. Volland/G.W. Parker

1913 – Bood of Bow-Wows, M. A. Donohue

1913 – Four Footed Folk

1913 – Mother Earth’s children, P. F. Volland

1914 – Butter Fly Babies, Rand McNally

1914 – Dolly and Molly and the farmer, Rand McNally

1914 – Dolly and Molly at the circus, Rand McNally

1914 – Dolly and Molly at the seashore, Rand McNally

1914 – Dolly and Molly on Christmas, Rand McNally

1914 – Granddad Coco Nut’s Party, Rand McNally

1914 – Watermellon Pete, Rand McNally

1915 – Loraine and the Little People of Spring, Rand McNally

1915 – A Sheaf of Roses, Rand McNally

1915 – What We Saw at Madame World’s Fair, S. Levinson

1916 – King Gum Drop or Neddies

1916 – I Wonder Why?

1917 – Wild Flower Children, P. F. Volland

1919 – Billy Bunny’s Fortune, P. F. Volland

1920 – Buddy Jim, Wise Parslow/P. F. Volland

1920 – Johnny Mouse’s trip to the Moon, P. F. Volland

1920 – Turned-Into’s, P. F. Volland

Dodge and Stilwell collaborate on “Rhymes and Jingles”

December 9, 2014

The 1904 edition of Rhymes and Jingles by Mary Mapes Dodge (1831-1905) was an exciting little volume with illustrated binding in gold embossed hunter green that features a little girl wearing a big decorated hat that attracts some whimsical butterflies. Beginning in 1874, Dodge served as editor of St. Nicholas magazine; she was credited with turning it into an American classic that spotlighted quality children’s authors and illustrators. Rhymes and Jingles was generously illustrated in black and white by Sarah S. Stilwell who employed a variety of artistic styling that reflected Howard Pyle’s illustrative sensibilities, but created a cohesive youthful take on Art Nouveau featuring a cast of fairy ladies, several working mice, and one awesome bubble-gum-popping girl:

Little Polly, always clever,

Takes a leaf of live-forever;

Before you know it

You see her blow it,

A gossamer sack

With a velvet back

How big it grows

As he puffs and blows!

But have a care,

It is full of air

Unless Polly should stop

It will crack and pop;

And that’s the end of the live-forever;

But little Polly is very clever.

Dodge described Stilwell as a “well-known artist” in 1904.

Source: Mary Mapes Dodge, Rhymes and Jingles (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1904).

Professional female networks

October 24, 2014

While women’s movement first organized on issues of women’s rights and suffrage, the movement has since worked for equality in employment opportunity and pay. In 1868, New York City journalist Jane Cunningham Croly was denied admittance to a dinner at an all-male press club, honoring author Charles Dickens based solely upon her sex. Croly soon organized a club for professional women called Sorosis, derived from the Greek meaning “a sweet fruit of many flavors”. Opportunities for professional or intellectual women to network were scarce, and by the end of the year, eighty-three women paid the $5.00 annual membership (equivalent to an average working woman’s weekly wage). The group met and Delmonico’s Restaurant, and regularly caused a stir because it was so unusual for an unescorted woman to dine in public. After the Civil War boom, the Beecher sisters with their American Woman’s Home (1869), attempted to direct women to prudently acquire and use the plethora of new consumer products available. The Beecher sisters felt that the chief cause of women’s social disadvantages was that they were not trained, as men are, for their peculiar duties, and the aim of their book was to “the honor and remuneration of domestic employment.”

In 1890, Croly and her Sorosis group invited women’s clubs throughout the United States to participate in a convention in New York. Sixty-three women’s clubs responded, resulting in the formation of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, which has since become a major volunteer service organization mobilized to promote issues related to civil rights and human rights. Moving into the twentieth century, women’s voices in regards to domestic work shifted radically as they fought for and obtained the vote. Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815-1902) was seventy-seven years old when she wrote The Solitude of Self (1892) after stepping down from the presidency of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Stanton recognized the political ramifications and psychological resources of “self” or of a woman having an individual life, ”Whatever theories may be on woman’s dependence on man, in the supreme moments of her life, he cannot bear her burdens.”

Homesteading and Women’s Social Networks

October 23, 2014

Women mobilized and moved to Kansas in an abolitionist effort to prevent the territory from entering the union as a slave state, and set an important precedent in 1861 when they gained the right to vote in school elections. During the Civil War, women took advantage of the Homestead Act (1862) and the Morrill Act (1862) to move into new territories and establish careers.

After the Civil War, Marietta Holley, using the pseudonym “Josiah Allen’s Wife,” emerged internationally as the bestselling American female satirist. Comparable in content and sales to Mark Twain, Holley’s work utilized exaggeration, the vernacular voice, intentional misspelling, and homely truths in her satire. Holley’s aggressive, loquacious, well-traveled, and plain protagonist Samantha Allen appeared two- dozen books published between 1872 and 1914. As a time when women fought for the vote, Holley spotlighted women’s networks in the private sphere. Holley’s character Samantha Allen was a Methodist, and favored prohibition and women’s suffrage. Methodism in the second half of the nineteenth century was in the midst of the Third Great Awakening when an enormous surge in membership occurred. Sect, in Holley’s secular usage, related to how men and women appeared to form distinct spheres within humanity by virtue of their common beliefs and practices. Samantha Allen. Samantha lived in Jonesville, a fictional town representing Middle America during the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Holley’s humor comes out in the way the rustic characters interact and are perceived in the world beyond Jonesville. Samantha is generally confronted with challenges that motivate her to journey beyond Jonesville in search of solutions, when Samantha brought her small-town common sense to big city issues, including the controversial ideas and networks of radical suffragists Victoria Woodhull who was a proponent for free love and spiritualism.